I

The Causes and Effects of Global Climate Change

Lesson - Climate Change’s Effects on Living Things

The atmosphere is a shared resource, which makes climate change an international problem. To deal with a global problem, policy proposals are made at multiple levels—international, national, and local. This makes agreeing on climate change policies difficult.

While climate change is a shared concern, it does not affect places and peoples evenly. There are great disputes about who should be held responsible for causing climate change and for repairing its damage.

Some countries are more vulnerable to the harmful effects of climate change than others. For example, Tuvalu—a country made up of nine small islands in the Pacific Ocean that is home to more than eleven thousand people—could become uninhabitable in the next fifty years as sea levels continue to rise. Within individual countries, impacts vary by region as well.

Even within local communities, some people may be more vulnerable to the effects of climate change than others. This often depends on where they live and how much their basic needs like food, water, and shelter are affected by changing climate conditions. For example, when Hurricane Sandy hit the United States in 2012, the people who were most affected were those in lower-income communities, such as those living in low-income sections of the Red Hook area in Brooklyn, New York. People in poorer neighborhoods may not have access to health care or the ability to evacuate their homes. Because of this, they tend to be more vulnerable than those who have greater means to recover from disasters.

In many countries, poor communities live in environmentally unsafe areas because this is where they can afford housing. In Nigeria, for example, poor people in the city of Lagos often end up living in swamps or the lowest-lying parts of the coast, where they are most exposed to flooding.

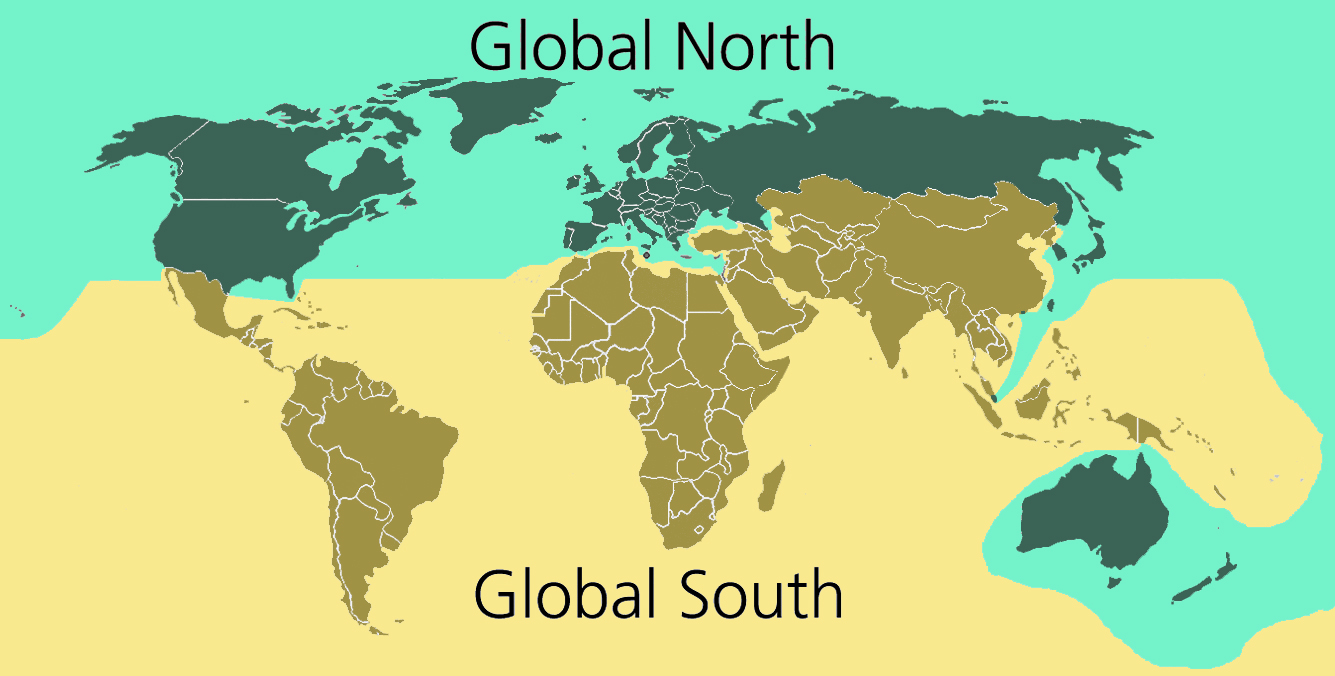

Poverty is important in determining vulnerability to climate change. From 2010 to 2013, people in the world’s forty-eight poorest countries were five times as likely to die from climate-related disasters. Poor countries are ill-equipped to deal with extreme weather and health issues. Because money is scarce, they often lack effective infrastructure (like hospitals and running water systems) to deal with the impacts of climate change, and their citizens often live in homes that cannot withstand intense storms. Most importantly, countries in the global South are the most likely to already be experiencing issues like water scarcity, food shortages, poor sanitation, and limited access to safe housing. Any worsening of these problems by climate change is likely to be catastrophic.

The thirty-two poorest countries in the world, which are home to 9 percent of the world’s population and often experience the greatest effects of climate change, are responsible for emitting less than 1 percent of total greenhouse gas emissions. This gap between responsibility and vulnerability complicates any response to climate change and raises important questions:

Developing [poorer] countries...are historically least responsible for the emissions that result in climate change, but most vulnerable to its impacts.”

Jessica Ayers, climate change researcher, “Resolving the Adaptation Paradox: Exploring the Potential for Deliberative Adaptation Policy-Making in Bangladesh,” 2011

The dispute over countries’ responsibility for past and future emissions is one of the most difficult issues in determining how to respond to climate change. It is costly to respond to climate change. Cutting emissions means putting limits on industry by demanding less use of fossil fuels, which few countries want to do.

For their part, the fossil fuel industry and multinational corporations contribute to the majority of greenhouse gas emissions. (A multinational corporation is a business enterprise based in one country that also has significant operations in at least one additional country.) According to a recent report, in 2015, one hundred energy companies were responsible for more than 70 percent of all greenhouse gas emissions.

Some activists call for “climate justice” in which countries pay the costs of dealing with climate change proportionately, depending on the extent of their responsibility for emissions. Those countries that contributed most to the problem would pay the most. Poorer countries, bearing less responsibility for greenhouse gas emissions, would pay less. But it is difficult to motivate wealthier countries to take responsibility, particularly given that they are the least vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

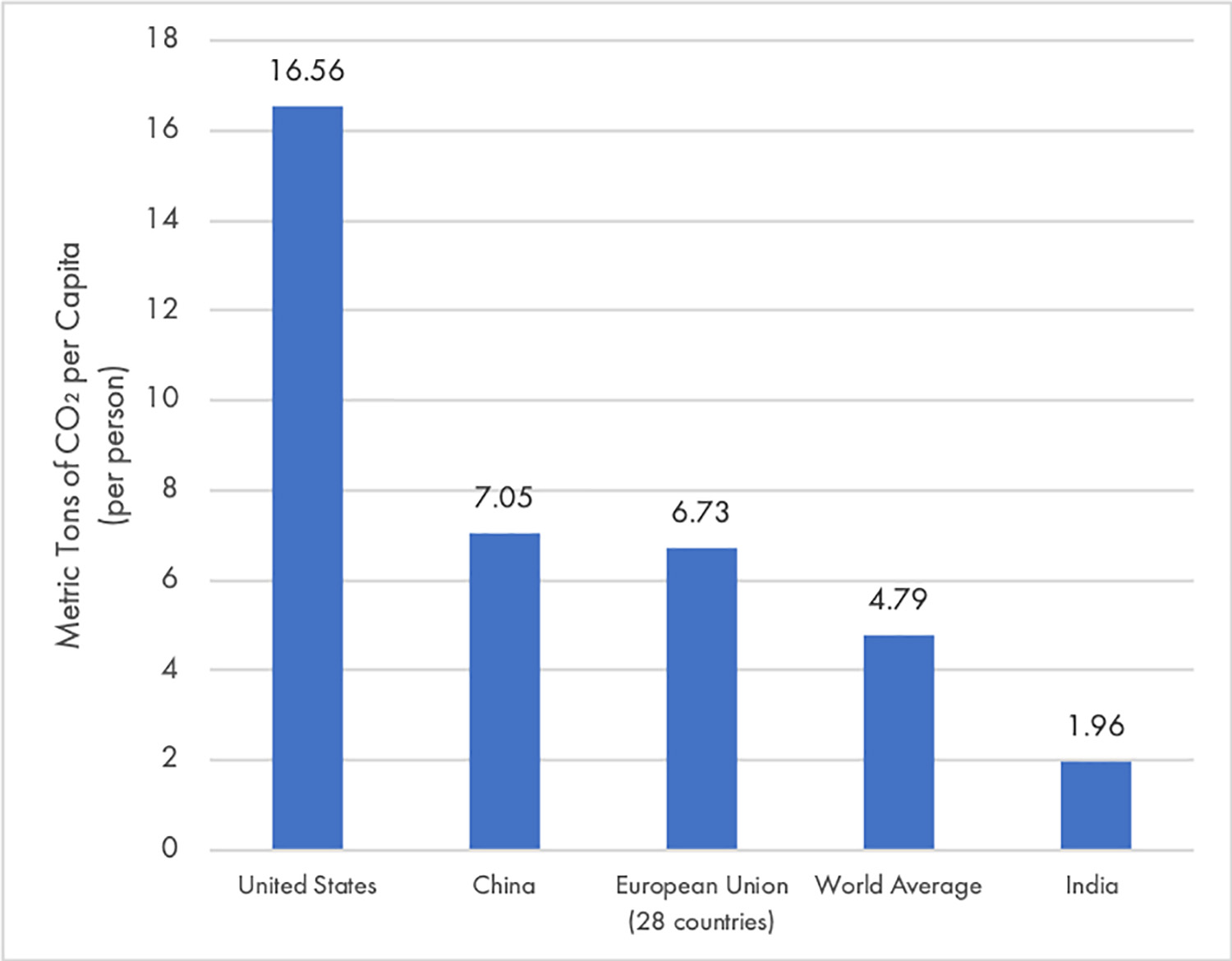

There is also dispute over how responsibility should be calculated. On the one hand, some believe that countries currently emitting the most greenhouses gases should be held responsible. This places much of the burden of responsibility on newly industrializing countries like China, which emits the most greenhouse gases in the world. On the other hand, China has a large population, which means it does not have the highest per capita (per person) emissions. Newly industrializing countries like China also do not have long-standing histories of greenhouse gas emissions the way countries like the United States do. Because there are different ways to define responsibility, it is difficult to decide how to create a response focused on “climate justice.” This raises another important question:

In 1992, in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, at what became known as the Earth Summit, 165 governments agreed on the principle of preventing dangerous climate change. In the years that followed, 196 countries ratified the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), an agreement to limit greenhouse gas emissions. The agreement stated that while climate change is a shared problem, different countries have different levels of ability to respond, and that wealthier countries should provide funds to address the problem.

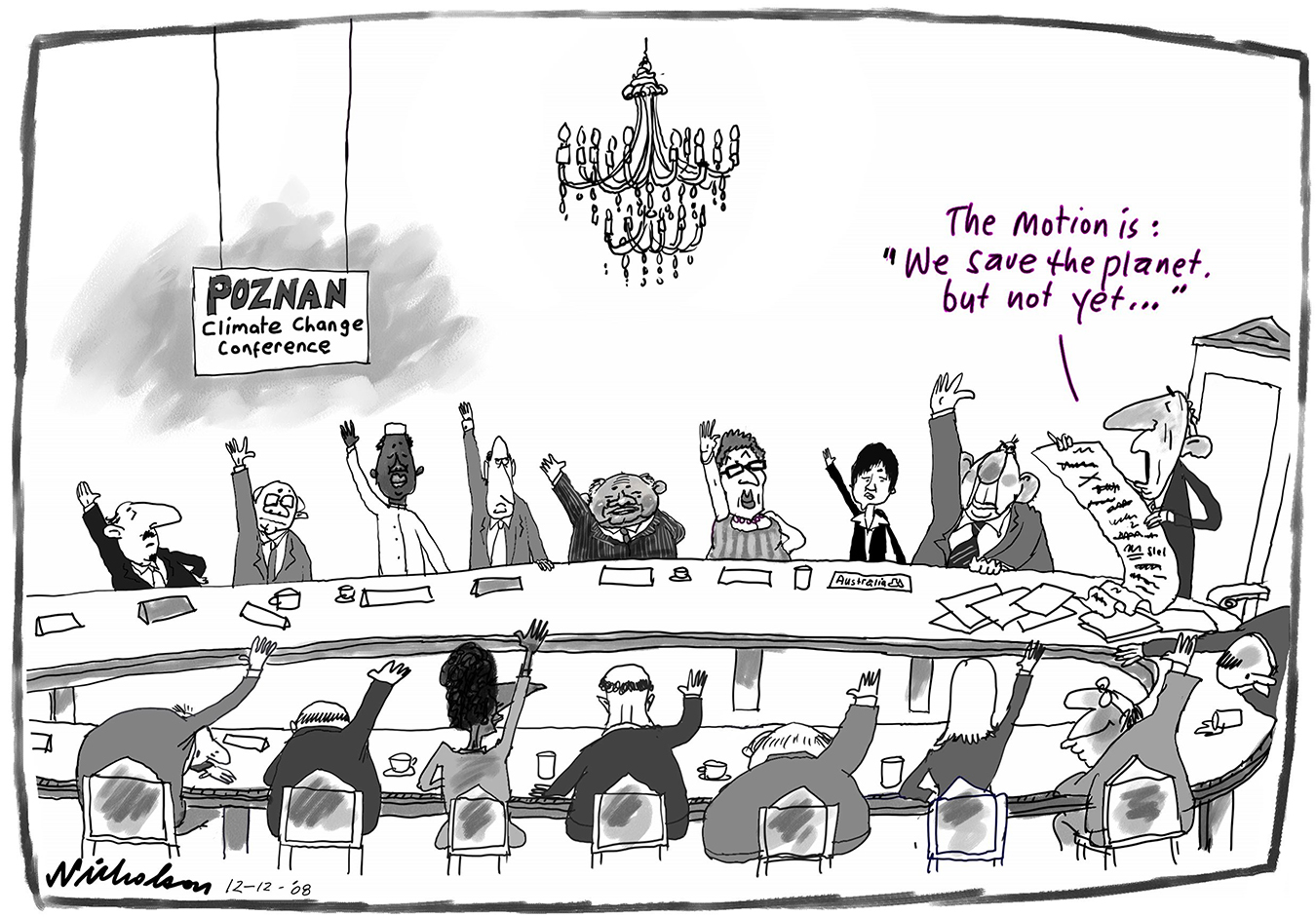

Most importantly, the UNFCCC created a system in which countries could continue meeting regularly in order to reach the general goals established in Rio. Each of these yearly meetings is referred to as a “Conference of the Parties” (COP). The COP meetings include government representatives, United Nations (UN) officials, activists, members of NGOs, and corporations that contribute to considerations of how to address the principles agreed to in 1992.

It has been difficult for countries to agree on how to limit greenhouse gas emissions and to decide who should make changes to prevent future problems. The economy of a particular country, its peoples’ values, and its political structure all contribute to its stance on climate change. For instance, the European Union believes that effective climate change policy must begin with widespread and immediate changes in national and industrial behavior to reduce CO2 emissions. Historically, the United States and Japan have preferred to focus on developing technology to protect and repair the atmosphere in the future. Poorer countries are primarily concerned with reducing their vulnerability to the effects of climate change.

Despite the principles laid out in the UNFCCC, one of the greatest obstacles in negotiations is deciding who is financially responsible—who should pay. It is initially expensive to reduce greenhouse gas emissions because it requires turning away from fossil fuels, which are currently the cheapest and most widely used form of energy. But it is also expensive to cope with the effects of climate change. (You will read about these effects later.)

Determining which course of action to take is particularly tricky because industrialized countries have already reaped the benefits of vast greenhouse gas emissions. This raises important questions:

One of the most significant international agreements, the Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC, has struggled to address these challenging questions.

The Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC, which was negotiated in 1997, laid out clear emissions restrictions for thirty-seven wealthier countries and reduction targets that poorer countries could volunteer to pursue.

Some countries have viewed the Kyoto Protocol as unfair, because it does not impose restrictions on China or India, both of which are substantial CO2 emitters. For this reason, in 2007, countries agreed that a new agreement must be drawn up to replace the Kyoto Protocol. In addition, many countries (including Canada and New Zealand) refused to submit to any more emissions restrictions under the existing protocol. The United States did not ratify the protocol at all, making the country exempt from all of the treaty’s commitments.

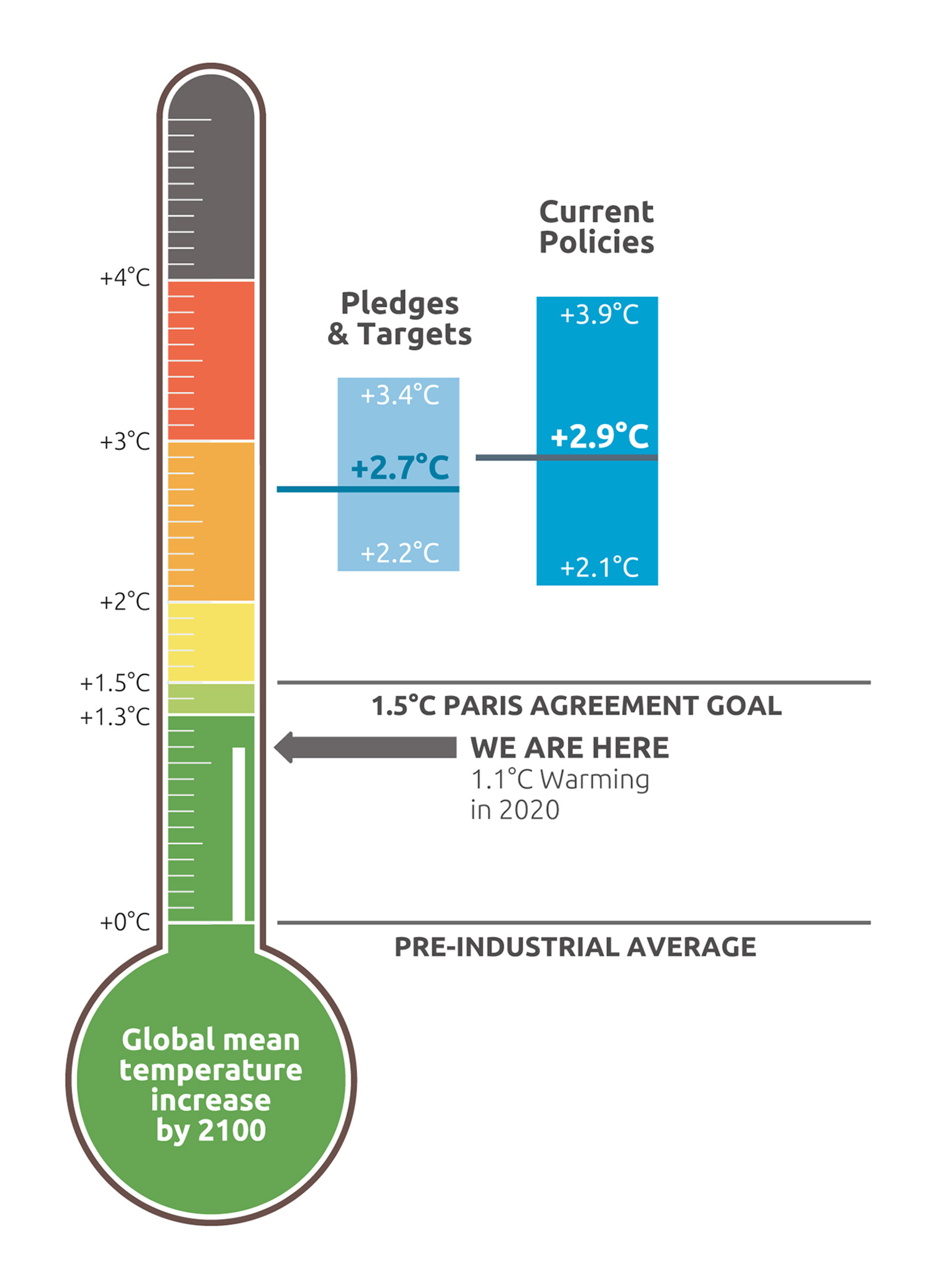

In 2015, representatives from 195 countries went to Paris for the COP 21. Their goal was to create an agreement to replace the Kyoto Protocol (which expires in 2020). Governments from all countries, rich and poor alike, agreed for the first time to create voluntary plans to reduce their domestic greenhouse gas emissions and provide funding for poorer countries’ programs to deal with the effects of climate change. The participation and cooperation of the world’s largest emitters of greenhouse gases, including China and the United States, helped ensure adoption of the Paris Climate Agreement.

In June 2017, U.S. President Donald Trump announced the United States’ intention to withdraw from the agreement. According to the rules of the agreement, a withdrawal could only take effect in 2020, one day after the 2020 U.S. presidential election. Trump opposed the agreement because he believed it was a bad deal that hurt the economy of the United States. Opponents of Trump’s decision included environmental NGOs and large corporations like General Electric, ExxonMobil, and Ford. A June 2017 poll by the Washington Post showed that 59 percent of the U.S. public opposed Trump’s decision, while 28 percent supported it. In November 2019, President Trump began the formal process of withdrawing from the agreement. President-elect Joseph Biden has pledged to rejoin the Paris Agreement on his first day in office in January 2021. Scientists note that even with the U.S. rejoining the Paris Agreement, countries will need to increase their pledges to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to meet the goal of limiting global warming.

Responses to climate change are generally categorized into two groups: mitigation and adaptation. The term “mitigation” means efforts to reduce the harm of something. Mitigation of climate change means reducing greenhouse gas emissions with the goal of preventing the harmful effects of climate change.

Many different mitigation strategies have been proposed and used over the past few decades. The production and distribution of many goods and services involves fossil fuels. For instance, plastic bags, water bottles, many plant fertilizers, clothing items, and many cosmetics are all made from oil. Reducing people’s demand for these things is one way of decreasing carbon emissions. Increasing energy efficiency (producing more energy with less fuel) across industries is another. Examples of this include using more efficient heating, cooling, and lighting systems in buildings.

Industry standards and regulations can be used to promote mitigation efforts. For instance, requiring certain levels of fuel efficiency for cars or changing building codes can decrease greenhouse gas emissions throughout an industry. Adding labels to products with information about how they were produced can also reduce emissions by educating consumers and perhaps changing what consumers choose to buy.

Another strategy involves reducing the emissions intensity of fuel sources. This means switching from fuels like coal and oil, which emit a lot of CO2, to fuels like natural gas, which emit less when used. But if careful measures are not taken, natural gas production can emit other greenhouse gases, like methane, erasing the benefits of burning natural gas.

Furthermore, increasing the use of zero-emissions energy sources is important in reducing the amount of greenhouse gases that end up in the atmosphere. Nuclear energy as well as energy produced from renewable sources like solar, wind, and water power do not emit any CO2 when used.

But zero-emissions energy sources come with their own set of problems. There are safety concerns about nuclear energy production and the storage of its radioactive waste. There is also a question of whether renewable energy can be produced at a low enough cost and a large enough scale to be widely used. Both businesses and people can be reluctant to pay more for zero-emissions energy if they can pay less for energy from fossil fuels.

Different types of policies encourage the use of these mitigation strategies. Several countries have implemented carbon taxes, which require emitters to pay fees for the amount of CO2 they emit. The money generated from the taxes can then be used to invest in other things, like the development of renewable energy.

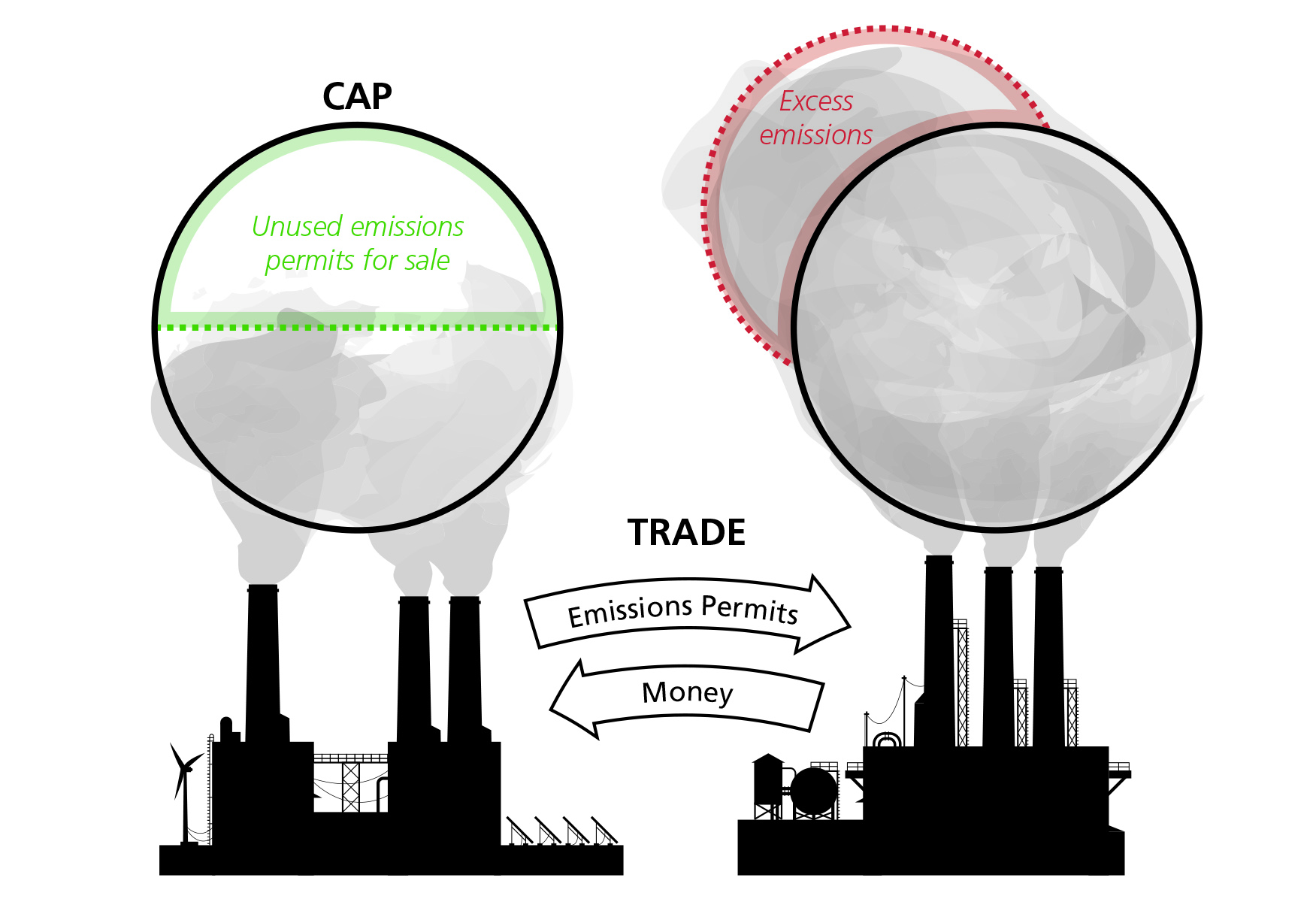

In cap-and-trade systems, a limit, or “cap,” to the total amount of emissions is set. Permits that allow companies to emit certain amounts of greenhouse gases are then either given away or auctioned off. If one company wants to emit more CO2 than it has permits for, it can buy permits from another company. Likewise, if a company does not need to use all of its permits, it can sell them to other companies. Both carbon taxes and cap-and-trade strategies attempt to put a price on carbon. If the price is too high, the economies of participating countries will suffer. If the price is not high enough, emissions levels will not drop significantly and may even rise in the long term.

While mitigation efforts are aimed at reducing the amount of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, adaptation focuses on adjusting to the effects of climate change.

In the decades following the 1992 Earth Summit, international leaders primarily directed their attention to mitigation. They hoped that through decreasing CO2 emissions, many of the potential negative effects of climate change could be avoided. Disagreements among countries about how to actually implement mitigation strategies have meant that progress on reducing greenhouse gas levels has been slow. Efforts to reduce emissions continue, but even if all human emissions of CO2 somehow stopped today, emissions from the past that have accumulated in the environment would still cause continued climate change. Scientists and policy makers have now recognized that mitigation alone is not enough.

The Cancún COP in 2010 declared that adaptation must be equal in priority to mitigation. This means that greater attention is now being paid to helping countries and communities adapt to the effects of climate change.

Adaptation strategies vary. Urban planners in coastal cities, for example, may take into account sea level rise and flood surges that accompany extreme storms. Farmers may plant different crops that are more resilient after droughts and floods. Governments might implement early warning systems for more frequent and intense extreme weather events and disease outbreaks.

Improved access to health care and economic opportunity are also important in reducing people’s vulnerability to the effects of climate change. For instance, creating new types of jobs in communities that have been dependent on fishing will make the problem of shrinking fish populations (caused by climate-related changes in ocean conditions) less catastrophic. People will have other options for how to make a living. Adaptation needs and priorities vary significantly depending on the environmental, social, and economic conditions of different countries, regions, and individual communities.

The increasing emphasis on adaptation, and the fact that adaptation needs are specific to particular places and peoples, has led to the development of National Adaptation Programmes of Action (NAPAs). The world’s poorest and most vulnerable countries have submitted NAPAs, which are plans that outline their most urgent needs regarding climate change adaptation, to the UNFCCC. Each NAPA consists of a ranked list of projects the country has identified as its highest priorities in adapting to climate change.

NAPAs, adopted at the COP in Marrakech, Morocco in 2001, focus on countries’ most immediate adaptation needs. Later, in Doha, Qatar in 2012, National Adaptation Plans (NAPs) were adopted by the COP to address more medium- and long-term projects to adapt to a changing climate.

The UNFCCC has a fund, provided by wealthier countries, to help poorer and more vulnerable countries develop and implement their adaptation plans. As of 2020, about $1.5 billion in funding has been approved, although this is not nearly enough to fund all of the adaptation needs of the world’s most vulnerable countries.

While decisions about the global response to climate change are made at the international level, NAPAs and NAPs depend on extensive input from local stakeholders (people and organizations who have an interest in or are affected by an issue). Both NAPAs and NAPs are intended as ways for members of local governments and communities to participate in making decisions about how their country will adapt to climate change. They are structured this way so that adaptation plans are not imposed from above, but rather driven by the concerns and priorities of the people in each country. For although climate change poses risks on an international scale, many impacts of climate change are experienced locally.

The lesson from climate change is...risks do not register their effects in the abstract; they occur in particular regions and places, to particular peoples, and to specific ecosystems.”

Professors Jeanne X. Kasperson and Roger Kasperson, commenting on how climate change affects people around the world differently, 2001

Finding a way for local communities to participate in decision-making about climate change adaptation on national and international levels can be challenging. This is because people and groups with more power, such as wealthy countries and international organizations, often see local communities’ expertise as inferior. For example, the top priority project in Bangladesh’s NAPA was to establish more forests in coastal areas to protect against sea level rise and more frequent extreme weather events. The NAPA process included input from people living in coastal communities, but their participation was mostly sought out to confirm what higher-up officials and other experts had already decided were the top concerns. As a result, this project focused on dealing with the physical effects of climate change, while the local stakeholders wanted instead to focus on improving social and economic conditions so they would be less vulnerable. In this case, the priorities reflected in the NAPA did not match those of the local stakeholders.

Sustainable development is a way of using resources that protects both environmental and human well-being in the long term. Responding to climate change—through both mitigation and adaptation—can present challenges for countries worried about it hurting their economic growth. Acknowledging this concern, international agreements and conferences have stressed the importance of sustainable development to combine economic improvement and climate change prevention. The goal of sustainable development is to meet the economic and social needs of the present generation without compromising or depleting resources for future generations.

In the case of climate change, this principle is particularly important as the most severe effects of today’s actions will most likely only be seen in decades to come. Fossil fuels, in particular, are not a sustainable source of energy. In addition to the harmful effects of the greenhouse gases released when people use them, the supply of coal, oil, and natural gas is limited. These energy sources take a long time to form, for they are made from the remains of plants and animals that lived millions of years ago. People are using them up at a faster rate than they are being regenerated, which makes humans’ current use of fossil fuels unsustainable over a long period of time. Furthermore, as they become less easily available, they will also become more expensive.

Sustainable development is a principle that many rich and poor countries try to follow. Some European countries, for instance, promote the use of bicycles to reduce reliance on fossil fuels. Efforts like this show that, in the global North, resources can be used sustainably without sacrificing a high standard of living.

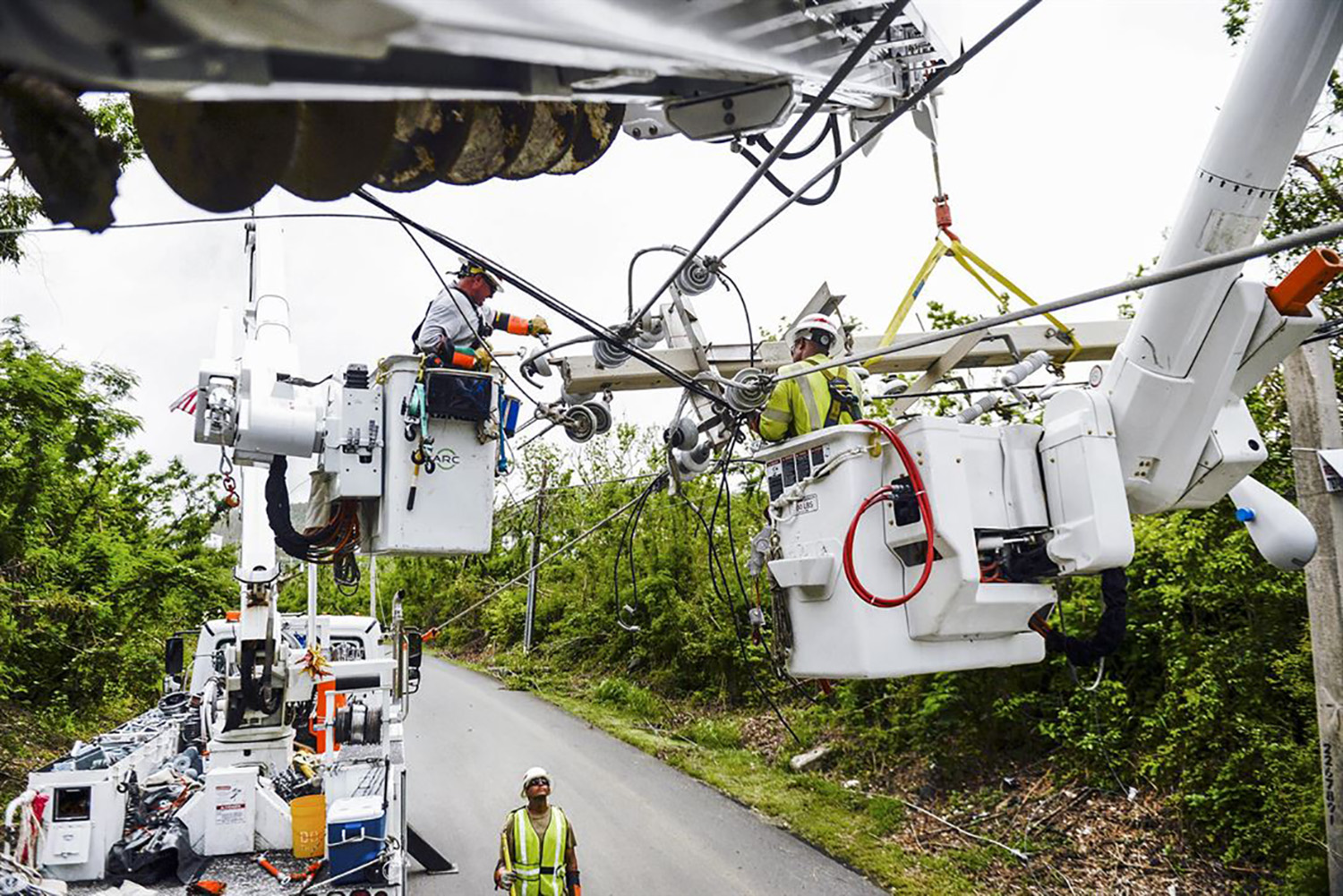

In the global South, renewable energy is an important aspect of sustainable development, providing struggling communities with effective and efficient power sources. For example, some regions of the Philippines use solar power to pump and purify drinking water. Remote villages in northern Peru generate electricity using the high levels of rainfall they experience. These sustainable development efforts both reduce the emission of greenhouse gases and provide employment opportunities.

Many policy makers and economists see sustainable development as a huge opportunity for the global South. They suggest that poorer countries can “grow green” by using technology that was not available when richer countries first industrialized. Because of this, sustainability is often included in the conditions of loans offered by wealthy countries to the governments of the global South. Sustainable development also has the potential to help many poorer countries become less reliant on foreign aid.

Frustration with the slow pace of the UNFCCC process to combat climate change has motivated other people and groups to propose their own responses. This has happened at different levels, from national governments to small interest groups to networks of activists. For example, nearly five hundred presidents of colleges and universities in the United States have vowed that their institutions will become carbon neutral (contributing no additional CO2 into the atmosphere). In many parts of the world, national and local governments are passing their own rules about climate change. Organizations, businesses, and individuals are also devising responses to climate change.

National governments: Some countries are deciding to take significant action on climate change despite the lack of legally binding international agreements. Denmark has vowed to end all fossil fuel use by 2050 and is a leading user of energy from wind turbines. Costa Rica, aiming to be carbon neutral by 2050, is shifting to electric vehicles and expanding its forests. It also imposed a carbon tax on fossil fuels. Part of the money from this tax goes toward forest conservation. The United States, though it is the largest historical emitter, has demonstrated less enthusiasm. In November 2014 under President Obama, the United States announced a new goal of reducing its emissions 26 to 28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. But in June 2017, President Trump announced that the United States would withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement and would no longer attempt to meet the emissions target of a 26 to 28 percent reduction. In 2020, President-elect Joseph Biden pledged to rejoin the agreement.

Local governments: Although the United States has been slow to take action on climate change at a national level, some individual states have not shied away from creating climate change policy. For instance, Massachusetts became the first state to place limits on greenhouse gas emissions from power plants in 2001. This led to the establishment of the country’s first cap-and-trade program, the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative, involving nine states along the East Coast of the United States.

In 2006, California passed the Global Warming Solutions Act, which required emissions be reduced by nearly 30 percent statewide by 2020. After reaching this goal four years ahead of schedule, in 2016 California enacted legislation to reduce emissions by 40 percent by 2030. Individual cities and towns are also making climate change a policy priority. After President Trump announced the United States would withdraw from the Paris Climate Agreement, the governors of twenty-four states and more than four hundred mayors announced plans to continue to try to meet the 2025 reduced emissions target.

Businesses: Governments are not the only institutions that have responded to concerns about climate change. Even businesses, long seen as the enemies of climate change policy, have become increasingly invested in reducing their impact on the climate.

When the Kyoto Protocol was signed, oil producers, vehicle manufacturers, and electrical trade associations vowed to prevent the ratification of the agreement. Because of their economic strength, they have had the political power to stall many mitigation policies. However, in September 1997, the oil corporation BP announced that it would voluntarily measure its emissions and research how to reduce levels of greenhouse gases.

By acknowledging the effect of fossil fuels on the environment, BP set off a revolution in how corporations approached climate change. Companies and industry representatives began to actively participate in the COP meetings and presented formal reports on their own attempts to fight climate change. Businesses began investing in forestry projects, which aimed to provide more CO2-absorbing plants, and started promoting the idea of emissions trading.

Some people claim that these companies are only trying to appear more environmentally friendly to improve their public image. For instance, while BP advertises its strong commitment to renewable energy, nongovernmental organizations such as Greenpeace have drawn attention to the fact that the company invests significantly less money in alternative energy sources compared with its investments in oil and gas. In addition, ExxonMobil, one of the world’s largest oil and gas companies, prominently advertises its commitment to reducing the risk of climate change. But at the same time, the company provides millions of dollars each year to organizations that promote the denial of human-caused climate change and to campaigns for politicians who are against climate change mitigation policies.

Many corporations continue to lobby against policies like carbon taxes. The amount of money oil companies put toward alternative energy is much less than what they spend to increase oil extraction. But the fact that some businesses are feeling pressure to present a new, green face and that customers are increasingly drawn to companies that express concern about the environment is significant.

The media: For a long time, media coverage of climate change, especially in the United States, attempted to balance claims of global warming with counter-claims that climate change was not real or that human activity was not causing it. This has declined as overwhelming scientific evidence of human-caused climate change has emerged.

Media coverage of climate concerns has expanded in recent years. This means people around the world have more access to information about climate science and how the atmosphere is changing. It also means that there is greater awareness of climate-related incidents such as severe storms. Because of the media’s growing emphasis on climate change, people around the world have become more aware of the dangers it poses to them and others.

Nongovernmental organizations (NGOs): Putting pressure on governments is one of the key functions of “green groups,” environmental advocacy organizations such as Friends of the Earth and Greenpeace. Like the media, these organizations are responsible for increasing public awareness of climate change. They frequently engage with people about their personal greenhouse gas emissions, as well as launching organized efforts to confront politicians. Other types of NGOs focus on providing on-the-ground assistance to communities trying to decrease their vulnerability or in climate change-affected areas that need disaster relief. Examples of these include Oxfam, Christian Aid, and the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies.

The influence of NGOs is becoming increasingly central to climate change negotiations on national and international levels. The number of organizations authorized to participate in COP meetings has expanded considerably over the years, including many from both the global North and the global South. In fact, at some COPs, representatives from NGOs have outnumbered government negotiators. At these meetings, the organizations take part in negotiation sessions, distribute reports, hold events, and interact with the press.

Growth in the number and diversity of organizations attending negotiations has led to greater influence for NGOs. But there are also divisions within the NGO community. These organizations do not have uniform priorities and often disagree on things like the viability of alternative energy or how to prioritize between mitigation and adaptation. NGOs, therefore, do not present a wholly unified force during negotiations.

New activism and activists: Frustration with the slow pace of the international and national responses to climate change has led to the growth of activism in recent years. For example, Fridays for Future, also known as the school strike for climate, is a youth-led global climate strike movement. Students skip school on Fridays to protest, demanding that political leaders take action to address the climate crisis. Fifteen-year-old Greta Thunberg began the strike in August 2018 in Sweden. Youth activists around the globe have joined. More than six million protesters worldwide joined in the Global Climate Strike of September 20-27, 2019.

Global climate change has been on the agenda of local governments, international leaders, and nonprofit organizations for decades, yet sometimes it can seem like little has been accomplished. Many significant obstacles stand in the way of responding to climate change.

Cost: Reducing greenhouse gas emissions can be expensive. Right now, fossil fuels are the cheapest source of energy. This is largely because of benefits called subsidies that governments provide. Subsidies make energy from fossil fuels cheaper to produce, lower the price consumers have to pay for that energy, and increase the price energy producers receive. Furthermore, fossil fuels are used in manufacturing goods, in generating electricity, and in other industrial activities central to a country’s economic growth. In comparison, other sources of energy, such as wind farms or nuclear power plants, are expensive to build.

Mitigation policies like carbon taxing or cap-and-trade systems attempt to make fossil fuels more expensive so that companies will find alternative energy more attractive. Unfortunately, this means that the price of products would increase, and neither businesses nor individual people want to pay more. If goods in one country increase in price, that country is at a disadvantage when trying to sell its products in global markets.

Many experts say that for mitigation to work, societies and cultures have to change in order to use less energy. This requires a transformation in how people live their lives, challenging the way homes are constructed, the kinds of food available to eat, and even the idea of individuals owning cars. Many people see this as a cost in quality of life. Ultimately, any sort of change will generate resistance. Even reducing a country’s vulnerability through adaptation, often seen as the “cheap” version of climate change policy because it does not scale down industry, demands funding. Obtaining this funding can be a serious challenge to governments and other organizations.

[I]t’s always easier to shell out money for a disaster that has already happened, with clearly identifiable victims, than to invest money in protecting against something...in the future.”

James Surowiecki, a journalist in the New Yorker, 2012

The North-South divide: The historical tensions between rich and poor countries can complicate the processes of climate change negotiation. While individual countries have different priorities and interests, poorer countries often feel they are not being treated fairly. Countries from the global South object when mitigation proposals restrict their ability to grow economically, making it harder for them to build roads, provide electricity, improve education, and create jobs for their citizens. They want the same opportunities that wealthier countries have had to pursue prosperity. Many poorer countries are also rightfully concerned about being overpowered in negotiations. The global North has more bargaining power in the international system—rich countries have the money to control world markets, which means they can control the economies of other countries. Wealthier countries often use their power to pursue their own national interests. Poorer countries, on the other hand, do not have the economic influence to push other countries to compromise. The result is that the most vulnerable countries have the least success including their interests in international agreements.

Most importantly, countries of the global South struggle to afford mitigation and adaptation projects, despite the fact that they will be most intensely affected by climate change. The countries that can afford these policies do not face such immediate or hard-hitting effects and therefore find the problem of climate change less urgent.

Political disagreement: Competition for political power often makes responding to climate change difficult. At the international level, government officials can be pressured by leaders from other countries, by economic concerns, and by groups of people within their own country who have strong and specific interests. These competing demands mean that even though the risks associated with climate change are clear, some leaders may end up prioritizing other issues in order to maintain relationships and power.

In addition, whatever agreements are accomplished at the international level ultimately come back to individual countries to carry out. For this reason, political conflicts at national and local levels also help determine what action people take to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

For example, there is strong partisan disagreement among politicians in the United States about climate change. The disputes include concerns about the impact of climate change mitigation on jobs and businesses, what role the international community should play in making policy, and even debates about climate science.

Furthermore, in many democratic countries, government leaders are elected every few years. It can be difficult for a country to make lasting decisions about climate change if its primary leaders change so frequently. Also, with politicians regularly up for re-election, they may choose to focus on issues that provide short-term benefits to the people who might vote for them as opposed to focusing on mitigation and adaptation strategies that are initially expensive but reduce longer-term risks. This way, a politician is more likely to retain his or her power and influence, even if the risk of dangerous future climate conditions continues to grow.

Additionally, certain industries have a stronger presence in some countries than in others. Some of these industries (like renewable energy and agriculture) may benefit from responding to climate change, while others (like oil and coal production) will not. This second category of industries can put immense pressure on government officials to make decisions that support the continued use of fossil fuels. Corporations in these industries do this through lobbying, providing funding for political campaigns that align with their interests, threatening to withdraw financial support from individuals or institutions if certain political decisions are made, and carefully crafting advertisements and publicity campaigns.

Communication: Climate change is a tricky issue for scientists, journalists, policy makers, and the general public to talk about. The concept of climate change can be hard to fully grasp because it refers to changes that occur over long periods of time. Because global warming’s effects may not be visible from one day to the next, climate change is less easily relatable to people’s daily lives and can be easy to ignore or put off until later.

You will never see a headline that says ‘Climate change broke out today.’”

Andrew Revkin, New York Times reporter, 2007

Furthermore, scientists who study climate change think about all the intricate details involved in the systems they study and often use highly specific terminology. As a result, they sometimes struggle to express to the public what the one or two main take-away points of their research are and why their findings matter.

Scientists are also trained to emphasize what they do not yet know and to make all potential uncertainties very clear. Government officials and journalists generally want to hear what scientists do know so that these discoveries can help inform important policy decisions. This tension in communication style often makes scientific conclusions about climate change appear less confident in the media than they really are. Scientists’ careful explanations of uncertainty get misinterpreted as meaning that they are not sure of their findings. This may be one reason why the broad scientific consensus about the dangers of climate change has been misrepresented.

Finally, climate change is often talked about as having potentially catastrophic effects. Emphasizing the dangerous impacts of climate change can make the issue feel overwhelming and hopeless. If people think that there is no possible solution to climate change, they may not be motivated to take action to slow or stop its effects. Thinking carefully about how people talk about climate change and making sure to highlight how much can be done is crucial to keeping people engaged with the issue.

You have read about the causes and effects of climate change, tracing its impacts on areas as varied as health, species migration, agriculture, and international security. You have explored contested understandings of who is responsible for global climate change, who is most vulnerable to its effects, and who has the ability to respond. You have also thought through different types of responses—mitigation and adaptation—weighing the pros and cons of each.

Climate change is a global issue with locally felt effects. While you have read about the complex web of international climate change conferences and the variety of local actors involved, you will next dive into case studies about how specific communities around the world are experiencing and responding to climate change.