The system of racial slavery did not emerge accidentally. A vast network of diverse people from across the Atlantic World created this system to suit their economic and political interests. Racial slavery can be directly linked to the efforts of Europeans to colonize territory in the Americas.

In Part I, you will read about European colonization of the Americas. You will examine how European colonists enslaved Indigenous people to work on their plantations and in their mines. You will also explore how colonists enslaved and forcibly relocated people from Africa, creating a system of racial slavery in the Americas.

Earlier forms of slavery were more diverse in terms of the labor performed and the ethnic background of enslaved people. In the Islamic World, only non-Muslims could be enslaved. The religious battles between Christians and Muslims during the Crusades, which spanned from 1095 to 1492, increased the enslavement of people with differing religious backgrounds. In this era, Christian European nations began to use “nonbelief” in Christianity as the primary justification to enslave people. In the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, some European powers like England and the Netherlands came to equate freedom and Christianity. Because of this, they passed laws or issued recommendations against the conversion of enslaved Africans to Christianity in order to justify their continued enslavement. Africans traditionally viewed slavery as a means to repay debts and as a political practice inflicted on captives taken in war. However, unlike European forms of slavery, African groups often attempted to incorporate enslaved individuals into their societies. The descendants of people enslaved throughout various African kingdoms therefore usually became free and equal members of these communities.

In many earlier forms of slavery the status of enslavement was not automatically passed to the children of enslaved people. In contrast, racial slavery in the Americas was heritable (passed through the mother to her child at birth) and legally defined as a permanent condition. By the 1660s, many European countries associated race with skin color, and slavery with blackness.

In the early stages of colonization, European powers like England also exploited prisoners, vagrants, and war captives for cheap labor. But over time, even these classes of laborers worked under set terms and protections from employers and the government. Most importantly, their status of servitude was not heritable, or passed onto their children through birth.

European colonization of the Americas began in the late fifteenth century. European nations were almost constantly at war during this period and throughout much of the colonial era. The colonization of the Americas was an extension of these conflicts over territory, wealth, and power. Although Europeans competed with each other, they waged wars and used other violent tactics much more often against Indigenous people in the Americas. European countries including Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, England, and France dispossessed and committed violence against Indigenous people. These forms of violence included, but were not limited to: killing, stealing land, enslavement, physical abuse, and cultural violence in the form of suppressing Indigenous traditions involving religion, food, family formation, and land use. As Europeans killed, enslaved, and violently removed Indigenous peoples from their land, they forcibly relocated Africans to the Americas and exploited their labor in order to profit from the land and resources.

Imperial powers including Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands, England, and France were in constant competition to achieve economic and political dominance.

These quests for wealth, power, and influence extended beyond the European continent and into the Americas, Africa, and Asia. Europeans created distinct ideas of racial difference as they encountered Africans, Asians, and Indigenous peoples throughout this process. The development of racial slavery is directly connected to Europeans’ colonization of the Americas.

I took by force some Indians from the first island, in order that they might learn from us, and at the same time tell us what they knew about affairs in these regions.”

Christopher Columbus, early European colonizer, recounts his first contact with Indigenous people, and their violent capture, in the Caribbean in 1493.

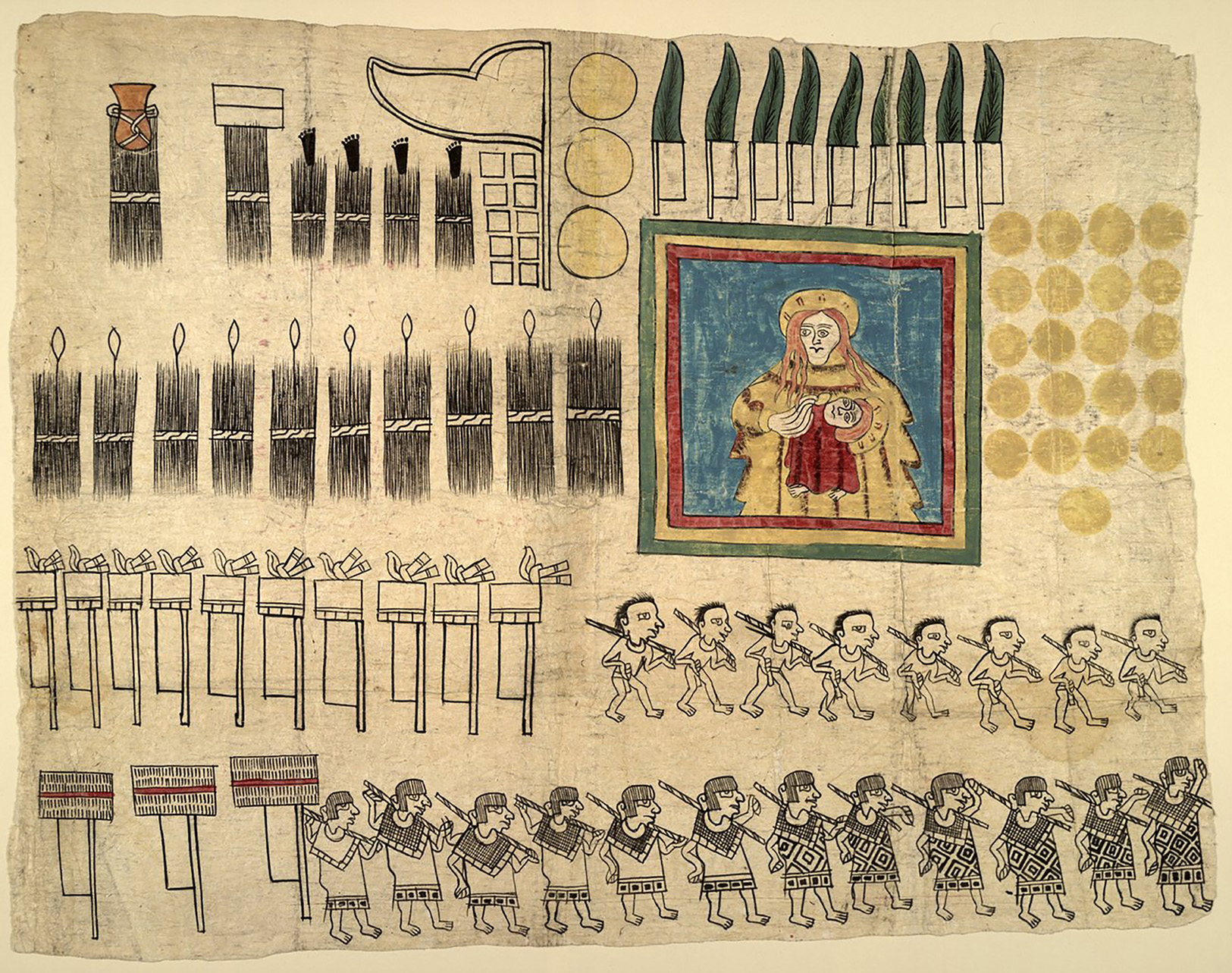

Colonization often included the dispossession, murder, and enslavement of Indigenous people. Colonial and religious authorities sought to convert the Indigenous people they encountered to Christianity and suppress their inherited religious practices. This process led to both physical and cultural violence against these communities.

European governments financed expeditions to prospective colonies in the Americas in search of wealth, such as gold and silver deposits or exportable cash crops. In the seventeenth century, colonists established a large number of plantations to produce cash crops. This drastically increased demands for laborers to cultivate and farm these lands for profit, particularly because Europeans had eliminated significant populations of Indigenous peoples through warfare, enslavement, and disease. Over time, many colonists increasingly relied on the forced labor of enslaved Africans.

We have pounded our hands in despair against the adobe walls, for our inheritance, our city, is lost and dead.”

Excerpt from a Mexica/Aztec poem, lamenting Spanish colonization and the devastation of the Mexica empire’s great capital city, Tenochtitlán (located where Mexico City resides today), sixteenth century. The Spanish would enslave many Mexica and other Indigenous groups, while forcing others in the region to make tribute payments in gold and silver.

Spain was the first European power to colonize parts of the Americas. Spain’s first colonizing efforts took place in the Caribbean, present-day Mexico, and Peru. In 1492, King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain sent an Italian named Christopher Columbus to find an easier sea route to Asian markets. Columbus’s ship instead landed on the island of Hispaniola, where he founded the first New World colony, La Navidad, located in present-day Haiti. Soon after Columbus returned to Spain, the Indigenous Taíno inhabitants of the island killed the European colonizers that he had left behind to form a colony.

A few decades later, Spanish conquistadors (conquerors) defeated the Mexica empire (in present-day Mexico)—referred to as “Aztecs” by Europeans—between 1519 and 1521 and the Incas (in present-day Peru) from 1532 to 1533. Spain quickly established a vast system of colonial administration to control these widespread territories. Spain claimed territory in modern-day Mexico, Central America, the Caribbean, and all of South America except Portuguese Brazil.

Colonial administrators forced Indigenous groups to make payments of tribute to the Spanish Empire, but Spain primarily acquired wealth through American silver and gold mines. For example, the Spanish obtained immense amounts of silver with forced Indigenous labor at the Potosí mines in present-day Bolivia. Silver from Potosí was traded around the globe, creating the first “world trade” network and serving as part of the financial foundation for the emerging capitalist economic system.

.png)

Portugal first established colonies in the Atlantic islands of Madeira, the Azores, and the Cape Verde islands in the mid-fifteenth century. These islands, considered part of Africa, provided a stopping point for sailors to reprovision their supplies and to rest before they continued to the African continent to trade for gold and spices. The Catholic Pope approved such missions to Africa between 1442 and 1456, and provided Portuguese traders with a religious justification to enslave people for profit. Beginning in 1500, Portugal colonized its first American possession, Brazil, and sugar cultivation took off shortly thereafter.

The Netherlands, England, and France were jealous of the massive mineral wealth that Spain extracted from its colonies. These countries all commissioned privateers—pirates hired or protected by a government—to seize Spanish silver shipments. Portugal and Spain dominated American colonization until the 1620s, when the Netherlands, England, and France launched colonization campaigns of their own.

.png)

The Dutch (Netherlands) established the colony of New Netherland (in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States today) in 1614. They initiated violent conflict with Algonquin tribes in order to preserve and extend their territory. Dutch colonists also forced enslaved Africans to work in New Netherland. The Dutch West Indian Company, a private company backed by the Dutch government, launched an ambitious plan to take over Portuguese colonies and their slave trade in the 1620s, seizing parts of Brazil and Portugal’s African territory in modern-day Angola. The Dutch also captured the Caribbean island of Curaçao from Spain. While the Dutch were eventually pushed out of Brazil, they retained their dominant position in the Atlantic slave trade for decades to come. They also led the way in the carrying trade, transporting goods between various European nations and their colonies. Dutch colonies in modern-day Suriname and Guyana in South America used enslaved Indigenous and African labor to produce and export cash crops. These colonies were essential to Dutch wealth throughout the eighteenth century.

England established colonies in North America and the Caribbean in the seventeenth century. These colonies lasted until the late eighteenth century (United States), mid-nineteenth century (Canada), and mid-to-late twentieth century (Caribbean). In Virginia, the English initially hoped to find gold mines like the Spanish had further south. When they failed to find gold, they shifted their attention to cash crops. English colonists in Virginia, Bermuda, and eastern Caribbean colonies such as Barbados and St. Kitts initially cultivated tobacco. After the 1650s, sugar production took off in Barbados and St. Kitts, and, in the early 1700s, expanded to Jamaica as well. Colonists in South Carolina, Virginia, and Maryland began using the model of plantation slavery established in the English Caribbean by the end of the seventeenth century. Caribbean plantation owners also brought management techniques developed first in Barbados—including specific violent tactics and strategies for controlling enslaved laborers—to the Carolinas and Georgia in the eighteenth century.

French colonization began in the sixteenth century in modern-day Canada with the aim of exporting fish. France established additional colonies in North America, the Caribbean, and South America in the seventeenth century. Early French colonists in North America largely focused on trade. This emphasis required them to develop relationships with local Native populations, but they also used physical and cultural violence against Indigenous people. French Caribbean possessions, such as Saint-Domingue (modern-day Haiti), Guadeloupe, Martinique, and St. Lucia, became the center of the French colonial system through the expansion of the slave plantation system on these islands. Caribbean plantations primarily exported sugar, a major cash crop, for profit.

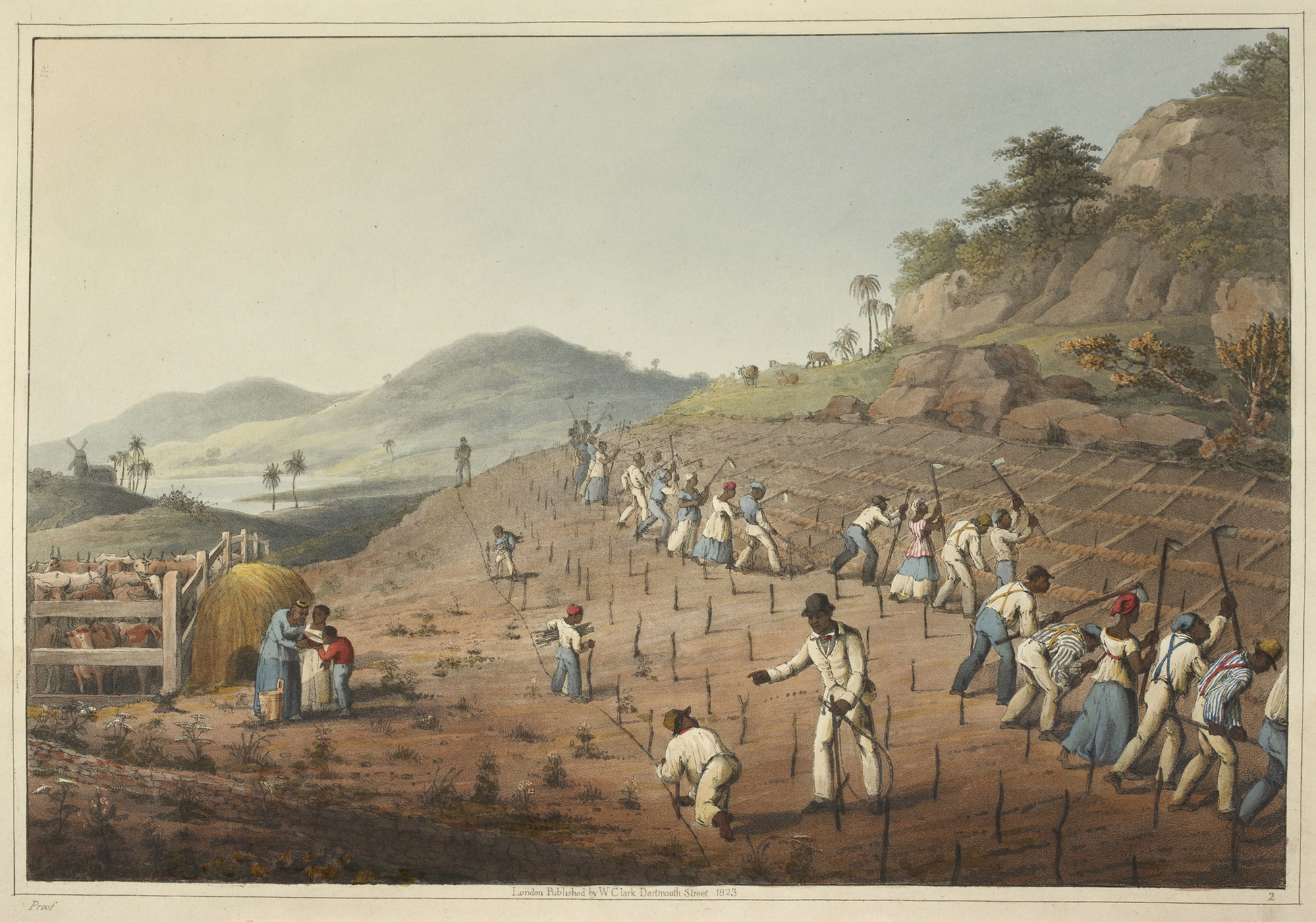

Profit was the driving force behind the trade in enslaved people and the slave system itself. As colonizers sought ways to make more and more money, they turned to cash crops, particularly those that were in high demand in Europe. The shift to cash crop production also included the development of new plantation management strategies. These strategies sought to standardize daily work patterns and squeeze every ounce of labor out of the enslaved workforce. Plantations were increasingly supervised by poor and middle-class white men who profited from their positions as plantation managers or “overseers.”

From the sixteenth through the nineteenth centuries, enslaved people produced cash crops including tobacco, cotton, indigo, rice, sugar, and coffee. Certain cash crops, such as sugar, cotton, and coffee, became more important over time due to increasing consumer demand in Europe. Not all colonies were designed for cash crop cultivation. Some colonies prioritized subsistence agriculture (producing crops for local consumption rather than export) for their colonizing settlers and the trade of basic goods such as corn, meat, livestock, timber products, and furs.

The most solid properties in Brazil are slaves and a man’s wealth is measured by having more or fewer…for there are lands enough, but only he who has slaves can be master of them.”

Luis Bahia Monteiro, Portuguese Colonial Governor in Brazil, 1729.

Spain and Portugal initially focused the agricultural systems of their American colonies (except Brazil) on basic trade goods and subsistence farming. As with elsewhere in the Americas, the Spanish and Portuguese relied on many crops, farming techniques, and agricultural systems taken from local Indigenous populations. Enslaved Africans also introduced crops and cultivation methods that were essential to the survival of these colonies. For the most part, sixteenth-century Portuguese colonies in the Americas were limited to small coastal regions. In Brazil, Portugal initially exported brazil wood (used for dyeing) when they failed to locate minerals like gold or silver. The dye from brazil wood was used in European textile (clothing) manufacturing, making it an essential product for early industrialization and the emergence of the modern capitalist economic system.

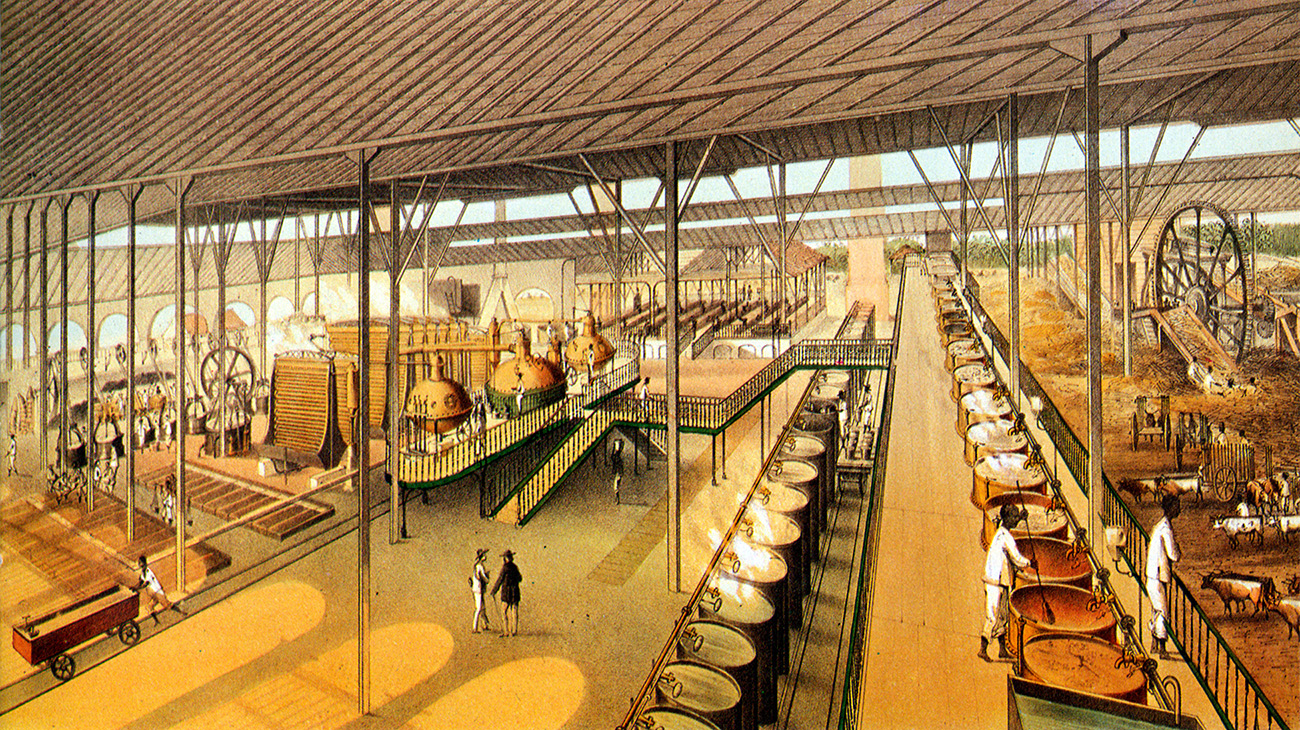

Everything changed when sugar cultivation increased in Brazil in the 1550s. Portuguese colonizers in Brazil developed a plantation system based on monocrop agriculture, or the cultivation, processing, and export of a single crop—in this case, sugar. Enslaved Africans planted, cultivated, harvested, and processed sugar, which brought Brazilian plantation owners great wealth. In other words, enslaved Africans were the foundation of the Brazilian economy. But sugar killed. Disease flourished in the hot tropical environment where sugarcane grew. These devastating illnesses combined with inadequate food rations and inhuman treatment by overseers to cause the average lifespan for an enslaved sugarcane worker in the early seventeenth century to be just three years.

The work is great and many die.”

Fernão Cardim, a Portuguese Jesuit priest, describing the devastating workload of enslaved African sugar plantation workers in Brazil, 1580s.

Like the Portuguese colonists, the Dutch, English, and French also sought a variety of profitable cash crops that they could sell in European markets. They found that sugar was the most enriching cash crop. During the so-called “sugar revolution” of the seventeenth century the English even started calling it “white gold.” Wealthy and middle-class Europeans fueled a “sugar craze” by massively increasing their consumption of sugar. This led to boosts in sugar production in the Americas and the forcible transfer of even more enslaved Africans. White consumers’ demand for the cash crops that enslaved people cultivated played an essential role in the slave system.

Three pounds of Brown Sugar, one pound of white powdered sugar made up in quarters, one pound of Brown sugar candy, one quarter of a pound of white sugar candy….”

Part of a list describing the contents of a trunk that Edmund Verney, a student at Oxford University in England, had shipped to him while he was at university in 1685. As a member of the upper class during an English “sugar craze,” Verney could demonstrate his wealth by consuming large amounts of sugar.

Spanish, Portuguese, Dutch, English, and French plantation owners in the Caribbean and South America largely turned to monocrop agriculture in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. They determined that large plantations were more profitable than small farms. The demand for laborers to work these extensive lands led to a boom in the Atlantic slave trade. The plantation system—and the racial slavery that served as its foundation—emerged in different forms in various places, and lasted well into the nineteenth century.

European colonizers quickly realized that their plans for monocrop agriculture required a tremendous amount of labor. They initially turned to the Indigenous populations of colonized lands. They enslaved Indigenous people to labor locally, or sometimes shipped them to other colonies with more drastic labor shortages. Because large portions of Indigenous populations died from European diseases, such as smallpox, colonizers began to seek other sources of labor, particularly through the enslavement of Africans.

European colonizers in the Americas often believed that Indigenous populations were inferior and subject to domination. Colonizers violently enslaved Indigenous people in their home regions, or shipped them elsewhere in the Americas for sale.

Europeans used the Bible to justify the enslavement of Indigenous and African people during the early phases of colonization. Many Europeans interpreted the Bible’s frequent references to slavery in ancient Israel as permission to enslave people in their own time. For example, Spanish colonizers attempted to justify their enslavement of Indigenous people by insisting they brought salvation to Indigenous groups through colonization and conversion to Christianity.

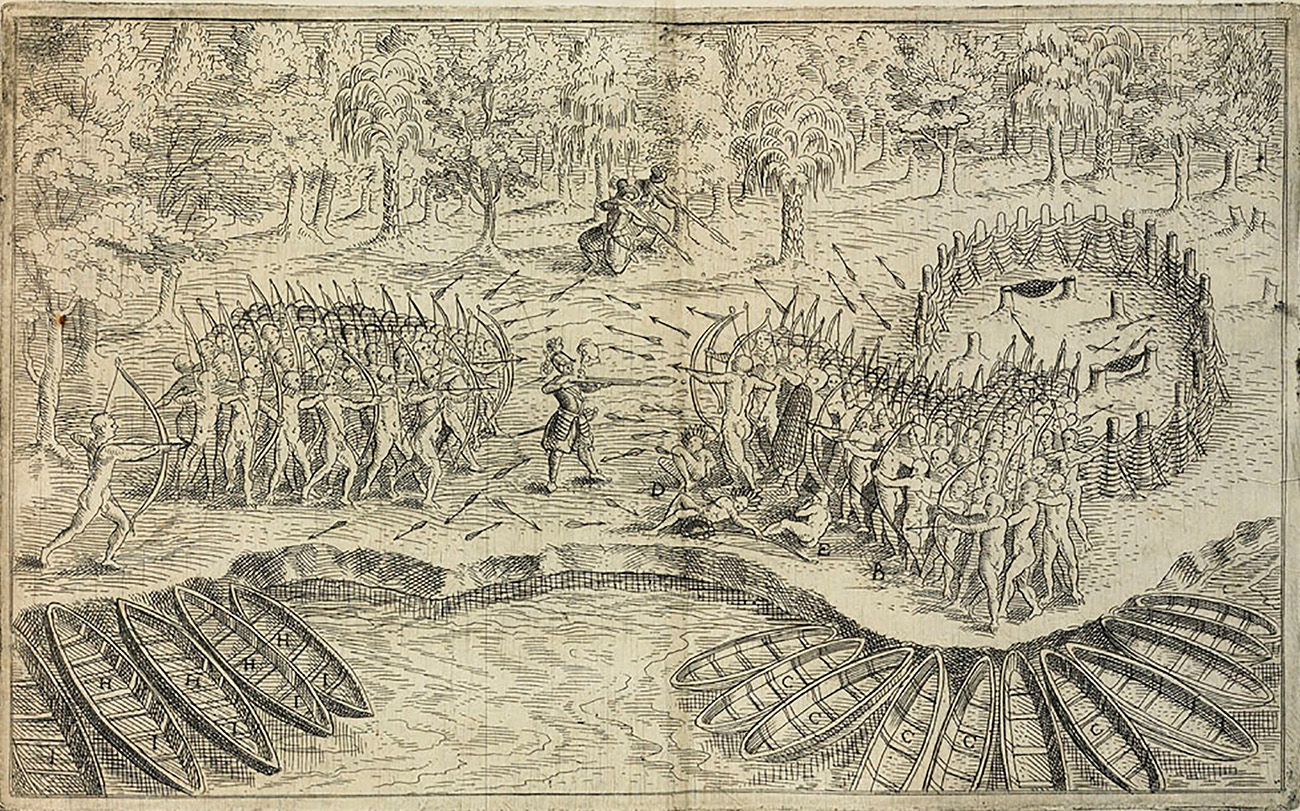

Colonizers also used the “just war” doctrine to explain their right to enslave Indigenous peoples. According to Christian religious doctrine, a “just war” was an ethical or righteous war. Europeans viewed their conquest of the Americas as righteous. They claimed that Indigenous people who resisted European colonization were prisoners of war who could be enslaved.

Servants, be obedient to them that are your masters according to the flesh, with fear and trembling, in singleness of your heart, as unto Christ.”

Ephesians 6: 5-7, a verse from the King James Bible that white Europeans used to justify enslavement.

By the mid-sixteenth century, some Spanish and Portuguese religious and political officials began to condemn the enslavement of Indigenous people in the Americas. Partly in response to these critiques and the shocking numbers of deaths of Indigenous people from European diseases, Spain passed the New Laws of 1542. These laws prohibited the enslavement of Indigenous people in Spain’s American territories unless they resisted Christianity or engaged in warfare against the Spanish. The New Laws did not bring an end to enslavement of Indigenous people in Spanish colonies. Spanish colonizers continued to use the “just war” doctrine to justify enslavement. Spain’s New Laws also did not affect the enslavement of Indigenous people in other European colonies.

[Spaniards] are still acting like ravening beasts, killing, terrorizing, afflicting, torturing, and destroying the native peoples, doing all this with the strangest and most varied new methods of cruelty, never seen or heard of before, and to such a degree that this Island of Hispaniola once so populous (having a population that I estimated to be more than three million), has now a population of barely two hundred persons.”

Dominican friar and priest Bartolomé de las Casas, describing the actions of Spanish colonizers in the Americas, 1542.

The enslavement of Indigenous people was just as extensive in Portuguese Brazil. Colonists forced Indigenous people to perform labor on plantations and public works such as roads, bridges, and churches. Colonists obtained enslaved Indigenous people through sale or widespread slave raids, in which armed colonists swept through Indigenous villages and violently seized people in order to enslave them. Indigenous people were also forced to live in Jesuit priest-run villages, called aldeias in Brazil, and work for the priests.

Like the Spanish New Laws had in 1542, the Portuguese Crown limited Indigenous enslavement in the 1570s. The Crown ruled that Brazil’s colonists could not enslave local Indigenous people unless they waged war against the colonists. Colonists ignored these laws and continued to enslave Indigenous people.

English, French, and Dutch colonists in North America and the Caribbean also enslaved Indigenous people, though not on the same scale as Spain and Portugal. Like the Portuguese and the Spanish, the English and French believed it was their duty to convert Indigenous people in North America to Christianity, though the English made less of an effort than the rest. English and French colonists enslaved Indigenous people to labor in homes, on farms, and for public works. English colonists in North America sometimes shipped enslaved Natives to Caribbean plantations, including captives from the Pequot War (1636-1638) and King Philip’s War (1675-1676). French colonists in New France primarily sought to trade with Native Americans for valuable beaver furs and convert them to Catholicism, rather than enslave them to work in mines or on plantations. Still, French colonists and Jesuit missionaries often used violence—or threats of violence—to compel Native Americans to acquire more furs, labor in French towns, or convert to Catholicism.

The harsh labor practices inflicted on Indigenous communities caused many people to die from overwork and disease. Some experts estimate that the Indigenous population of the Americas decreased from fifty to eight million people between 1500 and 1600. European diseases like smallpox, as well as the violence inflicted on Native communities, were responsible for the horrifically high death tolls. Rising death rates and Spanish and Portuguese religious prohibitions against enslaving Indigenous people inspired white colonists to seek other sources of labor. Indigenous people were also more likely than enslaved Africans to run away, as they were familiar with the local landscape and often had relatives in the area.

[Smallpox] brought great desolation; a great many died of it. They could no longer walk about, but lay in their dwellings and sleeping places, no longer able to move or stir.... The pustules that covered people caused great desolation; very many people died of them.”

Leaders of the Nahua (c. 1555), an Indigenous group in modern-day Mexico, reflecting on the smallpox epidemic that followed the Spanish invasion in 1519.

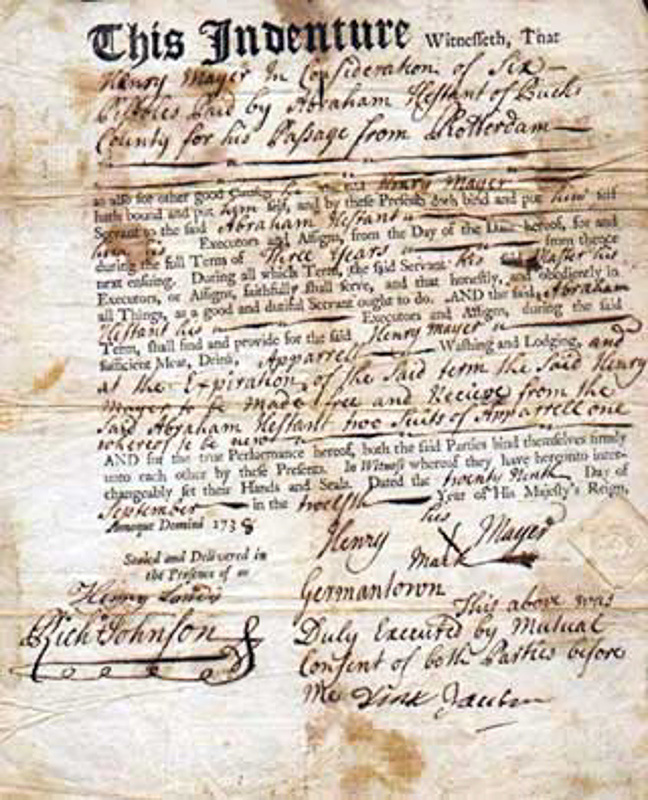

England and France turned to white prisoners (a practice known as convict labor), vagrants, and voluntary indentured laborers in the Americas. Indentured servants (known as engagés in French territories) were typically poor young men who—in exchange for travel to the Americas, room, and board—signed long-term contracts and agreed to work for four to seven years without pay. The unfavorable terms of the contracts resulted in many indentured servants being trapped by debt, forcing them to extend their contracts even longer. When the contracts expired, indentured servants were free to remain and work in the Americas, or to return to Europe. Though indentured servants were subject to mistreatment and abuse, their eventual freedom differed drastically from people subjected to enslavement.

Because the contracts of indentured servants were temporary and not permanent, plantation owners increasingly sought to use enslaved labor. White indentured servants were also able to run away more easily and blend into the community as free people compared to Africans, whose skin color marked them as enslaved in the eyes of white people. Finally, stories of harsh treatment of indentured servants reached Europe at the same time that there was a growing need for low-paid workers in Europe. Fewer young men were willing to sign indenture contracts. Seeking cheaper labor and larger profits, plantation owners in English and French colonies developed a clear preference for enslaved Africans by the closing decades of the seventeenth century.

The master of the ship sold your miserable petitioners, and the others;...they now generally grinding at the mills and attending at the furnaces, or digging in this scorching island; having naught [nothing] to feed on (notwithstanding their hard labour) but potatoe roots, nor to drink, but water...; being bought and sold still from one planter [plantation owner] to another, or attached as horses and beasts for the debts of their masters, being whipped at the whipping-posts (as rogues,) for their masters’ pleasure, and sleeping in sties worse than hogs in England, and many other ways made miserable, beyond expression or Christian imagination.”

Petition presented to Parliament in 1659 by Marcellus Rivers, Oxenbridge Foyle, and seventy other Englishmen accused of rebellion and sent to Barbados as indentured servants.

African slavery dramatically increased throughout the Americas in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. The expansion of sugar production and other cash crops increased the capture, enslavement, and forcible transfer of Africans from their homes to labor on American plantations. This connection between skyrocketing sugar production and increasing numbers of enslaved Africans can be seen in 1620s Portuguese Brazil, 1660s English Barbados, and 1660s French Saint-Domingue. Slaveholders from profitable sugar colonies also spread their plantation system and enslavement practices to other colonies. For instance, sugar plantation owners from Barbados migrated to English colonies in Virginia and the Carolinas, bringing their plantation practices and enslaved Africans with them. By the 1660s, plantation owners throughout the Americas had turned to enslaved Africans to perform the difficult physical labor of cash crop cultivation.

In American colonies, African slavery almost always followed the enslavement of Indigenous people and the use of white indentured servants and convict laborers. Racial slavery increased throughout the Americas in the seventeenth century but grew most rapidly in colonies with monocrop agriculture. Colonizers began enslaving Africans on a large scale in these colonies to produce cash crops, which quickly became the center of the Atlantic World’s capitalist economy. Europeans enslaved larger and larger numbers of Africans in order to expand their plantation systems in the Americas and enrich their empires.

By the early seventeenth century, European powers had established the system of racial slavery to confront labor shortages on their American plantations. By this time, European colonialism had killed millions of Indigenous people in the Americas through violence and disease. There were also not nearly enough indentured servants and convict laborers to meet the labor needs of the plantation system. Portugal and Spain, meanwhile, had imposed limitations on the enslavement of Indigenous people, partly due to their high death rates and partly due to their forced conversion to Christianity. Many colonial and religious officials believed that Christians should not be enslaved. Some of the same officials who argued for an end to Indigenous slavery in the sixteenth century called for an increase in the enslavement of Africans. They used Africans’ lack of Christian instruction as their initial excuse to enslave them.

By the middle of the seventeenth century, however, Europeans had created ideas about “race” to attempt to justify their enslavement of Africans. Europeans’ shift to primarily judging differences based on skin color enabled them to defend their creation of a permanently enslaved workforce whose status as enslaved people would be passed to their children. While cultural differences between Europeans and Africans could be reduced through conversion to Christianity, race was a visual marker of difference that could not be changed. After they began enslaving Africans on a large scale, Europeans formed racist ideas about people of African descent as particularly suited to laboring under harsh conditions.

The concept of “race” developed at different times across the Americas, but had clearly emerged by the mid- to late- seventeenth century. In the Americas, colonial authorities passed legislation to establish legal distinctions between black people and white people based on the concept of race. These laws strengthened and formalized racial slavery.

[B]aptism of slaves doth not exempt them from bondage; and that all children shall be bond or free, according to the condition of their mothers, and the particular direction of this act.”

“An act concerning Servants and Slaves,” a law passed by the English colony of Virginia’s General Assembly in October 1705. The law established that conversion to Christianity would not end a person’s status as a slave and that a child born to an enslaved woman was also enslaved.

By the eighteenth century, racial slavery that targeted African and Afro-descended peoples was firmly entrenched in Euro-American laws and society. Racial slavery was based on fictional ideas about race, but this construction of racial difference created the ideas of white supremacy and anti-black racism, resulting in horrific realities for generations of people of African descent. As you will read, racial slavery and the inequalities created by white authorities and plantation owners in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries continued to negatively impact people of color into the future and through to today.

In Part II, you will read about the economic, social, and political circumstances that led to the expansion of the transatlantic slave trade. You will also read the accounts of several enslaved people who endured the horrifying conditions of the Middle Passage and subsequent forced separations from loved ones in the Americas.