III

Case Studies

Readings

Study Guides and Graphic Organizers

Lesson - Looking at the Eight Case Studies

The case studies you are about to read are not meant to be exhaustive or comprehensive. They are designed to highlight a range of effects climate change has on people and places around the world, to consider what factors in specific situations shape the effects of climate change, to think about how these factors interact to increase vulnerability of specific groups of people, and to explore various methods of response.

Each case study includes a table with basic information about the country covered. For those that focus on cities or states, information about the specific regions is included in the text of the case. You will be given the population of each country and its gross domestic product (GDP) per capita. GDP per capita is an estimate of the economic output per person within a country and gives a sense of a country’s economy and its citizens’ incomes. A higher GDP per capita generally means the population of that country is more wealthy and the government has more money for pursuing various policies. A lower GDP per capita, on the other hand, suggests a poorer population with limited government funds.

In addition to population and GDP per capita, the table for each case will show the average person’s life expectancy and the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions per capita (per person) in that country. Use the information in these tables as you consider each case and compare it with others. As you read, keep these questions in mind:

After reading these case studies, you will begin to consider what responses to a changing climate, both locally and internationally, you believe to be most fair and effective.

With over thirty-nine million people, California has the highest population of any U.S. state. If it were a country, its economy would be sixth largest in the world. Both of these factors contribute to California’s ability to influence the rest of the United States, helping it set policy trends that the rest of the country may soon follow. Californians have a history of being interested in environmental issues. This public support has helped the state lower its emission levels. (In 2017, California emitted 9.2 metric tons of CO2 per capita, while the U.S. average was about 16 metric tons.) Looking more closely at California can help show how mitigation policies can be established locally, rather than at the international level.

| United States | |

|---|---|

| Population | 328 million |

| GDP per Capita | US $65,118 |

| Life Expectancy | 78 years |

| CO2 Emissions per Capita | 16.1 metric tons |

California is experiencing a number of climate change’s effects—flooding, lower crop yields, extreme heat, drought, and wildfires—which are expected to worsen in the coming century.

The hots are getting hotter, the drys are getting drier. Climate change is real. If you are in denial about climate change, come to California. Eleven thousand dry lightning strikes over a seventy-two-hour period, leading to this unprecedented challenge with these wildfires. This is an extraordinary moment in our history. Mother Nature has now joined this conversation around climate change. And so we need to advance that conversation anew.”

California Governor Gavin Newsom, speaking about the challenges California faces from climate change, August 21, 2020

In addition, California is already prone to drought, and climate change may make future droughts more intense. Political conflicts have erupted within the state as well as between California and its neighbors about how scarce and precious water resources should be shared. A drought that lasted from 2011 to 2019 caused tens of thousands of farm workers to lose their jobs and cost the agriculture industry well over four billion dollars. Hot, dry conditions also increase the risk of wildfires, which can destroy people’s homes. Some experts predict that the area of land in California affected by wildfires will increase significantly in the next hundred years.

Fundamentally the science is very, very simple. Warmer and drier conditions create drier fuel. What would have been a fire easily extinguished now just grows very quickly and becomes out of control.”

Philip B. Duffy, a climate scientist and president of the Woodwell Climate Research Center, September 13, 2020

California has taken the lead on climate change mitigation within the United States. In 2006, California passed a law called the Global Warming Solutions Act. The law required that by 2020, the state reduce its greenhouse gas emissions to the levels they were in 1990. California met that goal in 2016 while continuing to have a growing economy. Its 2020 emissions are nearly 30 percent less than they would have been without the law, bringing the state close to what the Kyoto Protocol would have required.

The law also includes a statewide cap-and-trade system for major emitters, one of the first in the United States. This program is seen as a “test case” that has shown that a cap-and-trade system can successfully curb emissions without hurting the economy. Environmental regulations in California have influenced national policies in the past. The success of this program increases the chance that the United States could adopt a similar program nationally.

Establishing California’s Global Warming Solutions Act was not easy. Even after the law was passed, it was nearly overturned. Oil companies, even those from other states, funded much of the opposition to the law. These companies claimed their disapproval was fueled by concern that the law would cause many Californians to lose their jobs. But many others, including California’s governor at the time, believed the companies were worried that their own profits would suffer under the law.

Does anyone really believe that these companies, out of the goodness of their black oil hearts, are spending millions and millions of dollars to protect jobs?... It’s not about jobs at all, ladies and gentlemen. It is about their ability to pollute and thus protect their profits.”

Former Governor of California Arnold Schwarzenegger, 2010

Oil companies were not the only groups that resisted. Some environmental groups were concerned that the cap-and-trade system did not put strong enough limits on emissions. They feared that it would be ineffective in mitigating climate change and that it would not do enough to stop oil companies from polluting areas where many poor people live. Despite so much controversy, the law remained in effect, and California implemented its cap-and-trade system in 2013.

In 2019, the state’s cap-and-trade program generated $2 billion (through companies’ purchase of emission permits). California put this money toward other climate change mitigation and adaptation projects, and more than 50 percent of the money will go toward programs that benefit poor communities. The state has also partnered with the Canadian province of Quebec—linking their cap-and-trade systems together—and plans to continue joining with other programs.

California continues to push forward in climate change mitigation. In 2015, California announced a new goal for the state, calling for 50 percent of its energy use to come from renewable sources by 2030. The following year, California enacted legislation to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to 40 percent below 1990 levels by the year 2030. In 2020, Governor Gavin Newsom signed an executive order banning the sale of new gasoline-powered cars by 2035. Even though California is not a national government, the state is providing a model for mitigation on a national and international scale.

The People’s Republic of China is the world’s largest country by population size and the second largest by land area. Across provinces there is huge variation in culture, living standards, and environmental conditions.

For more than thirty-five years, China’s economy has been steadily growing, which has drastically reduced poverty. At the same time, there has been a rise in inequality between China’s rich and poor. The case of China illustrates the impact of economics on both vulnerability to and responsibility for climate change.

| China | |

|---|---|

| Population | 1.4 billion |

| GDP per Capita | US $16,785 |

| Life Expectancy | 77 years |

| CO2 Emissions per Capita | 7.2 metric tons |

The impacts of climate change in China are often overlooked in the local media and in political discussions. Nevertheless, climate change affects China in many important ways. The country faces risks of flooding, extreme weather, and food and water scarcity. Some scholars have even claimed that China is the country most vulnerable to the effects of climate change. China’s meteorological administration has said that in parts of the country, the speeds at which temperatures are rising have consistently topped the global average.

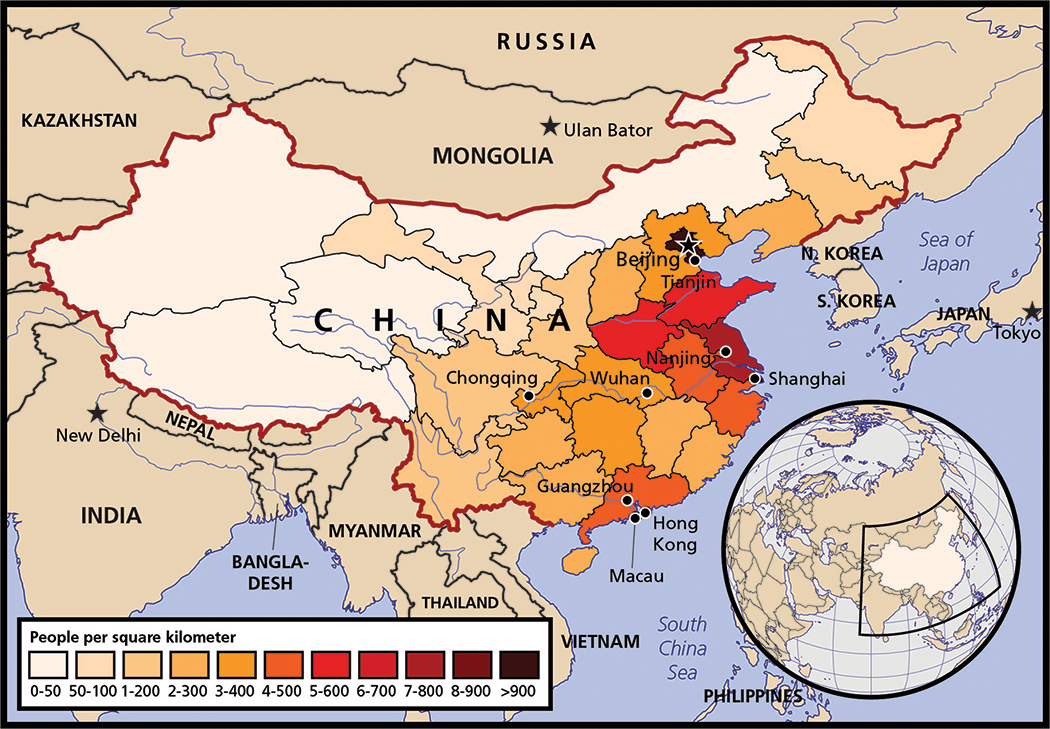

Dramatic temperature increases mean that people in China can expect to experience severe social effects of climate change. Some of the most densely populated cities in the world are situated along China’s coast. The city of Shanghai, for example, has a population density of more than 9,900 people per square mile (far exceeding Los Angeles’ population density of 8,200 people per square mile). In addition, the rural areas surrounding these coastal cities have much larger populations than inland areas toward the west. Because of the concentration of people living along the coast, sea level rise threatens the homes of eighty-five million people (more than the entire population of the United Kingdom).

China’s strict residential laws (known as the hukou system) that limit the ability of people to migrate could make this even more devastating. In particular, it is very difficult to move from rural areas in the countryside to a city. Rural residents are much poorer than those who live in the cities. Many of these rural economies offer few employment options other than farming. As a result, people in rural areas are hard-hit by crop failures caused by extreme weather or changes in the lengths of seasons. Additionally, a lack of hospitals and other services and infrastructure means that rural residents find it extremely difficult to recover from the effects of climate change. These factors, combined with how difficult it is for people to leave rural areas, make China’s rural population especially vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

Despite China’s vulnerability to many dangerous effects of climate change, the Chinese government has been reluctant to commit to strong mitigation agreements. This is because China’s economy is dependent on manufacturing that requires a great deal of energy and that relies largely on coal. Until the rapid economic growth of the past thirty-five years, China was a very poor country. It has used the rapid expansion of industries to relieve poverty. Promising to sharply reduce emissions from fossil fuels might slow China’s economic growth.

China’s historical reluctance to increase its mitigation efforts have had international consequences. For example, the main reason that the United States refused to ratify the Kyoto Protocol was that the treaty did not require emissions reductions from countries in the global South, like China and India.

We still have 150 million people living below the poverty line and we therefore face the arduous task of developing the economy and improving people’s livelihood. China is now at an important stage of accelerated industrialization and...we are confronted with special difficulty in emission reduction.”

Former Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao, at the Copenhagen Climate Summit, 2009

In fact, China currently emits the most greenhouse gases of any country, accounting for about 28 percent of the world’s CO2 emissions. This is partially because it has a large population; the amount of greenhouse gas emissions per person in China is actually less than half that in the United States.

China’s status as the “factory of the world” also contributes to the country’s high emissions levels. Many of the products used across the world are manufactured in China, so some people claim that emissions have been “exported” to China. This means that despite China’s position as the biggest emitter, it may not be the most responsible for climate change because it is merely emitting gases on behalf of the countries that are buying its goods.

But China has demonstrated an interest in reducing its dependence on fossil fuels. In November of 2014, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced a joint emissions reduction agreement with U.S. President Obama. This was China’s first ever commitment to cap its CO2 emissions and paved the way to its agreeing to sign the Paris Climate Agreement in 2015. In September 2020, President Xi Jinping announced a pledge that China would become carbon neutral by 2060.

In addition, China has invested heavily in alternative energy. The country has become the world’s leading investor in renewable energy technology both at home and abroad. China now produces more wind turbines and solar panels than any other country. China wants to be at the forefront when renewable and zero-emissions energy sources become more widely used globally. Its goal is to grow economically by providing all of the technology for this type of energy.

Furthermore, China has an interest in reducing its use of fossil fuels like coal because they are causing thick smog in many Chinese cities. This smog makes people sick, reduces tourism, and makes the public frustrated with the government. China is already experimenting with some cap-and-trade schemes in cities suffering from smog problems. By March 2017, it had shut down all coal plants in Beijing, although coal plants continue to be built in other parts of China.

Colombia was part of a territory under Spanish colonial rule until it gained its independence in 1819. Throughout the nineteenth century, this territory broke up into multiple smaller countries until the Republic of Colombia as it is today emerged in 1903. Colombia is now the fourth largest country in South America by land area and the third largest economy on the continent. Over the past two decades, economic growth has improved living standards for many, but a large portion of its population lives in poverty. The country has highly varied geography, with densely populated mountainous regions in the northwest, tropical rainforests that are home to many different plant and animal species in the southeast, and low-lying coasts on both the Pacific and Atlantic Oceans. Its economy is based on exporting goods such as petroleum, coal, emeralds, coffee, bananas, and clothing. In fact, it is the fifth largest coal exporter in the world. Despite a history often marked by political conflict and violence, Colombia’s economy has been growing steadily, and it is becoming a more important player on the global stage. Studying how climate change affects Colombia can demonstrate how climate change affects human health.

| Colombia | |

|---|---|

| Population | 49 million |

| GDP per Capita | US $15,644 |

| Life Expectancy | 77 years |

| CO2 Emissions per Capita | 2.03 metric tons |

Because of the diversity of landscapes present in the country, Colombia is experiencing a wide range of climate change’s effects. Between 1983 and 2013, increasing temperatures shrunk the glaciers (large masses of slowly moving ice) in the Colombian Andes Mountains by almost 60 percent. Today, these glaciers are melting even more quickly. From 2002 to 2007, Colombian glaciers shrunk, on average, by three square kilometers each year. At this rate, experts project that most of these glaciers will completely disappear in the coming decades. This affects the amount of water available for drinking and farming as well as for electricity generation (around 70 percent of the electricity produced in Colombia is from hydropower). In addition, like in many other coastal countries, flooding from sea level rise could displace many people and cause huge losses in the croplands that are vital to Colombia’s economy.

Humanity’s greatest challenge is to either work together to preserve this planet or destroy it. It’s up to us to assume our own responsibility and defend life.”

Colombian environmental activist Francia Márquez, August 19, 2019

Colombia may also experience some of the health effects of climate change. About 22 percent of Colombia’s population is at risk of malaria infection, a disease that affects more than 240 million people around the world each year. Malaria can be deadly if not treated quickly, and in many parts of the world, malaria medicines are no longer effective to treat it. In 2018, 405,000 people died from the disease worldwide, two-thirds of them children under the age of five. A certain type of mosquito spreads the parasite that causes the disease, and where these mosquitoes are able to live is highly dependent on climate conditions. While the environmental factors that determine where mosquitoes live are highly complex, both the malaria parasite and the mosquitoes that carry it generally thrive in warm temperatures.

For decades, the disease has been present only in Colombia’s lower elevation regions, and its overall prevalence has even decreased throughout the country. Nevertheless, as temperatures have risen over the past few decades, more cases of the disease have emerged at higher elevations. With warming temperatures, the mosquitoes that spread malaria may be able to live in the higher, traditionally cooler, areas of the country—bringing malaria to those regions where it had not been common before. This means that climate change may put the dense populations of Colombia’s mountainous regions at greater risk of malaria.

Our latest research suggests that with progressive global warming, malaria will creep up the mountains and spread to new high-altitude areas.”

Menno Bouma, London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, 2014

Before the mid-2000s, Colombia focused primarily on climate change mitigation projects that were also seen as economic opportunities. For example, it participated in programs that allowed wealthier countries to assist with projects, like new fuel-efficient bus systems, to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in Colombia. These projects helped Colombia pursue sustainable development while also helping wealthier countries reach their emissions reduction goals to prevent continued global climate change.

Colombia’s response to climate change has recently shifted. In 2010 and 2011, the country experienced devastating rainfall, flooding, and cold from a cyclical climate condition called La Niña, which shifts ocean and air temperatures in the southern Pacific into a roughly ten month cold phase. The intense flooding affected four million Colombians and caused more than US$7 billion in damages related to loss of livestock, homes, and infrastructure. It is not clear how La Niña (and its warmer counterpart, El Niño) is linked to global warming, but the extreme weather made people in Colombia more concerned about the effects of a changing climate. After this environmental disaster, Colombia shifted its focus to adaptation. This is similar to other countries in South America, like Uruguay, where recent climate-related disasters led government officials and the public to pay more attention to climate change.

We only produce 0.4 percent of CO2 global emissions, but we are one of the most vulnerable countries on climate change effects.”

Colombian President Iván Duque, June 27, 2019

Colombia has now made climate change adaptation a national priority. Policies to combat the effects of climate change are integrated into many country-wide plans and projects. For example, Colombia created an Adaptation Fund to help farmers recover from the damaging effects of climate change, and in 2017, began to implement its National Adaptation Plan for the UNFCCC. In addition, as part of the Colombian National Pilot Study of Adaptation to Climate Change, the country has increased its malaria monitoring and prevention efforts. Colombia has recently developed new maps, mathematical models, and early warning systems to help plan for changes in patterns of malaria exposure. Collaborations between government ministries that focus on climate and those that focus on malaria are increasing. Because of these efforts, Colombia has become internationally recognized as a leader in South America on climate change issues.

Freiburg is a wealthy city in the southwest of Germany that is home to many university professors. Nearly 12,000 of its 230,000 inhabitants work in environmental management or environmental science, including renewable energy research. With the average income in Freiburg almost 30 percent higher than the rest of Germany, the city generally has a high standard of living and has become internationally known for its environmentally friendly practices. For example, in 2005, per capita CO2 emissions from transportation in Freiburg were only 29 percent of the U.S. average.

Because Freiburg was heavily bombed during World War II, it had to rebuild much of its infrastructure after the war ended. This means that many of the buildings and roads in Freiburg today were constructed relatively recently, some with environmental concerns in mind. Freiburg serves as an example of how carefully thought-out city planning can enable changes in lifestyle and make possible a highly developed urban community without harmful greenhouse gas emissions.

| Germany | |

|---|---|

| Population | 83 million |

| GDP per Capita | US $56,052 |

| Life Expectancy | 81 years |

| CO2 Emissions per Capita | 8.84 metric tons |

With over 1,800 hours of sunshine each year, Freiburg is one of the hottest, sunniest locations in Germany. Climate change is expected to increase the risk of heat-related health problems like heat stroke in southern Germany. There also may be more forest fires. In addition, fresh water will become more scarce in the region in the coming century, especially during the summer. On the other hand, Freiburg is within a major wine producing region of Germany, and global warming is expected to help the grape harvest. Overall, these environmental impacts are much less severe and immediate than in many other parts of the world. This makes adaptation less of a priority for the people of Freiburg, allowing them to focus more on mitigation strategies.

Freiburg has worked to minimize its impact on the environment for decades. As early as 1996, city officials declared that Freiburg would strive to reduce its CO2 emissions by 25 percent by 2010. Although it did not quite meet this goal, the city is now striving for a 40 percent reduction of emissions by 2030. Even more ambitious, it is hoping to become carbon neutral (contributing no additional CO2 into the atmosphere) by 2050.

A sustainable urban and transport policy, as well as an effective climate protection and environmental policy, are founded on a number of cornerstones: energy from sustainable sources, attractive and sustainable transport provision and low-energy standards in house-building, to cite just a few examples…. This approach is driven forward by the inhabitants of the city, whose commitment and involvement represent the foundation of a viable and sustainable community. Freiburg has become the model ‘Green City’ for many cities and towns worldwide.”

Freiburg Mayor Dieter Salomon, 2017

Freiburg is an international hub for research on renewable energy sources, especially solar. Solar panels are on many buildings—businesses, universities, private homes, churches, city hall, and even the soccer stadium. Some of the city’s electricity is also produced by processing trash.

Some sections of Freiburg have gone even further in their efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The Vauban quarter is a region of Freiburg built in 1998 that is close to the city center. There are no parking spots on the streets, and many people in Vauban do not have cars. (The city has an extensive public transportation system, and bikes are very popular.) The few people who do have cars must purchase expensive parking spots, which are very limited. Houses are specially designed to minimize energy needs, and cooperative living is common. This builds community among the residents, many of whom take pride in their environmentally friendly lifestyle.

While Freiburg has taken some dramatic steps toward sustainability, it is just one of many cities across the globe that is trying to reimagine how urban life and the natural world can more harmoniously coexist. This is especially important because by the year 2050, more than two-thirds of all people worldwide will live in cities.

Freiburg is a member of ICLEI-Local Governments for Sustainability, an international association of cities and local governments dedicated to sustainable development. While the ICLEI (International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives) is currently based in Germany, its member cities and towns are spread across the world in over eighty countries. This type of international organization helps create partnerships among cities so they can learn how other places are working toward reducing CO2 emissions and building greater resilience against the effects of climate change.

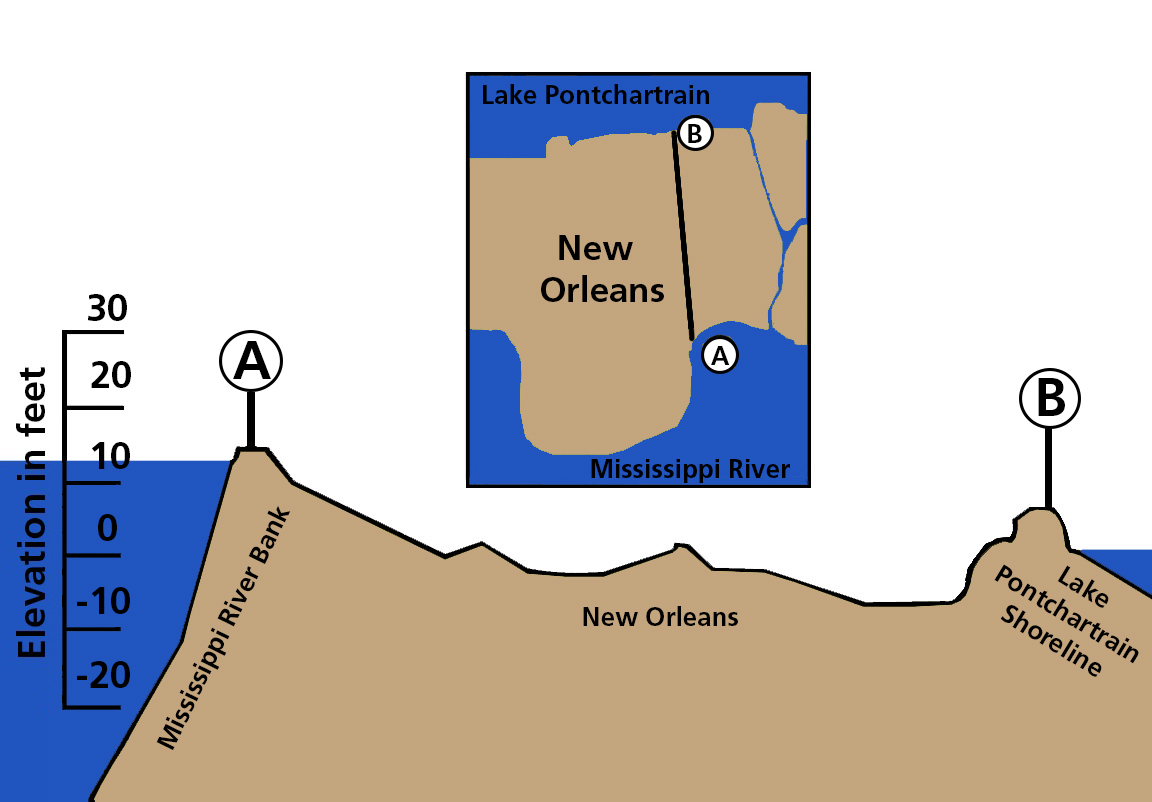

New Orleans is a major port and Louisiana’s largest city, with a population of over 390,000. The majority of the population is Black. Located on a delta of the Mississippi River, New Orleans is sandwiched between Lake Pontchartrain to the north and the Gulf of Mexico to the south and east. Much of New Orleans lies several feet below sea level and depends on levees (natural or artificial ridges made of soil and sand that line a body of water to prevent water from overflowing) and floodwalls to keep the city dry.

For years, New Orleans has struggled with high levels of poverty and racial segregation—as of 2020, 25 percent of the population was living in poverty, more than twice the national average of 11 percent. Furthermore, it is the city’s Black residents who are disproportionately affected by poverty. The city has become deeply segregated based on income with certain neighborhoods housing poorer residents and other neighborhoods housing the wealthy. Looking more closely at how New Orleans is experiencing and responding to climate change shows the dangers that U.S. coastal cities face—and how this danger is amplified for residents who are poor or people of color.

We were abandoned. City officials did nothing to protect us. We were told to go to the Superdome, the Convention Center, the interstate bridge for safety. We did this more than once. In fact, we tried them all for every day over a week. We saw buses, helicopters and FEMA trucks, but no one stopped to help us. We never felt so cut off in all our lives. When you feel like this you do one of two things, you either give up or go into survival mode. We chose the latter…. No one is going to tell me it wasn’t a race issue. Yes, it was an issue of race. Because of one thing: when the city had pretty much been evacuated, the people that were left there mostly was Black.”

New Orleans evacuee Patricia Thompson, reflecting on her experience of Hurricane Katrina, December 6, 2005

| United States | |

|---|---|

| Population | 328 million |

| GDP per Capita | US $65,118 |

| Life Expectancy | 78 years |

| CO2 Emissions per Capita | 16.1 metric tons |

Experts have identified New Orleans as one of the cities most vulnerable to rising sea levels. (Other U.S. cities that are especially vulnerable include New York, Miami, Los Angeles, and Seattle.) Since Europeans first established the city more than three hundred years ago, New Orleans’ coastal location and low elevation have made the city vulnerable to storms and floods. The earliest European settlements were built on the higher elevation shores of the Mississippi River. But as the city expanded, people constructed homes at lower elevations. Although the city has a long history of confronting storms and floods, scientists predict that New Orleans will be increasingly threatened by changes in the global climate. Rising sea levels pose a growing challenge for the low-lying city, and scientists project that hurricanes coming off the warming waters of the Gulf of Mexico will be more frequent and severe.

In addition to its history of flooding, like many cities in the United States, New Orleans also has a history of racial segregation and structures that systematically disadvantage people of color and poor people. For example, certain policies, such as those related to housing, have segregated the city’s residents by race, often forcing them to live in areas vulnerable to flooding. In August 2005, Hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans. Levees and floodwalls were breached, and water surged into the city. About 80 percent of New Orleans flooded, with some places under more than twelve feet of water. The structural failure of the levee system, coupled with inadequate warnings and insufficient rescue operations, had disastrous effects for residents.

The hurricane claimed over 1,800 lives, mostly in the New Orleans area, and forced nearly 1.5 million people to evacuate. Within one month of the hurricane, people from New Orleans were seeking refuge in every state of the country. While Katrina caused intense flooding in most New Orleans neighborhoods regardless of race or wealth, areas stricken with poverty were least able to cope with the effects of the hurricane. In poorer, majority-Black areas, people often did not have access to cars or other forms of transportation as the hurricane approached, leaving many stranded and unable to escape. Twenty thousand people went to the Superdome stadium for refuge, but the shelter was prepared for far fewer people.

Each day, it was a battle to find enough food and water and get it to the Superdome. It was a struggle meal to meal because, as one was served, it was clear to everyone that there was not enough food or water for the next meal.”

Marty Bahamonde, a FEMA field officer who responded to the disaster, reflecting on the storm before Congress, 2005

Of those who died as a consequence of the storm, 67 percent were Black, reflecting the breakdown of the population of New Orleans at the time. Many of the neighborhoods that were hit the hardest and where the most people died were predominantly Black. Black neighborhoods had been historically relegated to the low-lying areas of the city.

Although scientists generally do not attribute specific extreme weather events to climate change (and therefore do not say that climate change caused Hurricane Katrina), climate change will increase the frequency and intensity of storms like Katrina in the coming century.

The intensity of the storm, combined with the failure of the government to respond adequately, led many to suggest that New Orleans and the United States were ill-equipped to deal with the effects of climate change.

What amazed many worldwide was that these extensive failures, often attributed to conditions in developing [poorer] countries, occurred in the most powerful and wealthiest country in the world.”

Community and Regional Resilience Initiative Research Report, 2008

Members of the Congressional Black Caucus, the National Urban League, the National Council of Negro Women, the NAACP, and the Black Leadership Forum gathered after the storm to discuss the U.S. government response to Hurricane Katrina. They agreed that the government responded slowly and inefficiently, and they suggested that race played a major role in this response.

To support the claim that the government’s response has been dictated by systemic racism, people have cited specific examples. For instance, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) gave trailers to about 63 percent of the residents of St. Bernard Parish—a majority white area. At the same time, FEMA only gave trailers to 13 percent of residents in the Lower Ninth Ward—a mostly Black area also destroyed by the storm.

Many people across the country began to view the destruction from Hurricane Katrina as closely tied to systemic racism (see box) in the United States.

We have an amazing tolerance for Black pain.”

Reverend Jesse Jackson, in an interview speaking about the disproportionate suffering of Black people during Hurricane Katrina, September 2005

The severity of Hurricane Katrina and the destructive toll it took on the city of New Orleans sparked a national discussion about how to prepare for the city’s future in the face of a changing climate. These conversations have largely focused on ways New Orleans can adapt to climate change, as opposed to how it can increase mitigation.

Local and national attention has focused on rebuilding the city to be better prepared for rising sea levels, stronger storms, and changes in precipitation patterns. Efforts include elevating existing buildings by several feet, constructing new escape routes through roofs, and improving emergency response plans. In the years following Katrina, Congress approved funding for multibillion dollar engineering and construction projects to build floodwalls, water pumps, and a chain of levees over one hundred miles long to protect New Orleans from future storms. The projects, designed to protect against a one hundred year flood, were completed in 2018. However, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers believes that the new protection will not be enough to withstand the rapid pace of climate change and sea level rise by 2023. While many people have returned to the city, some areas of the city have not been rebuilt.

Since the disaster, some activists and policy makers have worked to get the public and the government to acknowledge the role that racism and racist policies have played in increasing the vulnerability to climate change for populations of color. They have also called for policies that combat poverty and racial segregation in U.S. cities, including New Orleans.

The conservation and restoration of coastal wetlands are also important for increasing New Orleans’ climate change resilience. For centuries, coastal wetlands (areas of swamps and marshes) provided a natural barrier to storms and flooding for residents of New Orleans. Today, the rate of the loss of wetlands in New Orleans is among the highest in the world—on average an area of wetlands the size of one football field is lost every hour. Oil and gas industries have destroyed wetlands by dredging canals (deepening canals by scooping out mud and sand from the bottom) and building thousands of miles of pipelines in coastal Louisiana. Levees and dams on the Mississippi River have slowed the flow of sediment from the river that restores wetlands.

Many nongovernmental groups have pressed the state and federal government to do more to halt the destruction of these crucial wetlands, not only for the sake of wildlife, but for the sake of residents in New Orleans and the region. Some strategies would be to plant more cypress trees and marsh grasses along the coast as well as to divert water from the Mississippi River to replenish the wetlands with sediment. However, because these diversions would impact local people and businesses, determining where they should occur is challenging. Without significant action, much of coastal Louisiana could be underwater by the end of the century. This makes clear just how important local adaptation efforts are in the face of international leaders’ failure to take strong action against climate change.

In New Orleans, we are all too familiar with the damage being done and the risks at stake. Climate change impacts our quality of life, our public health, and it disproportionately hurts those with the least resources. I am proud to...demand that every level of government take meaningful, equitable action for cities and for our people.”

LoToya Cantrell, mayor of New Orleans, December 3, 2019

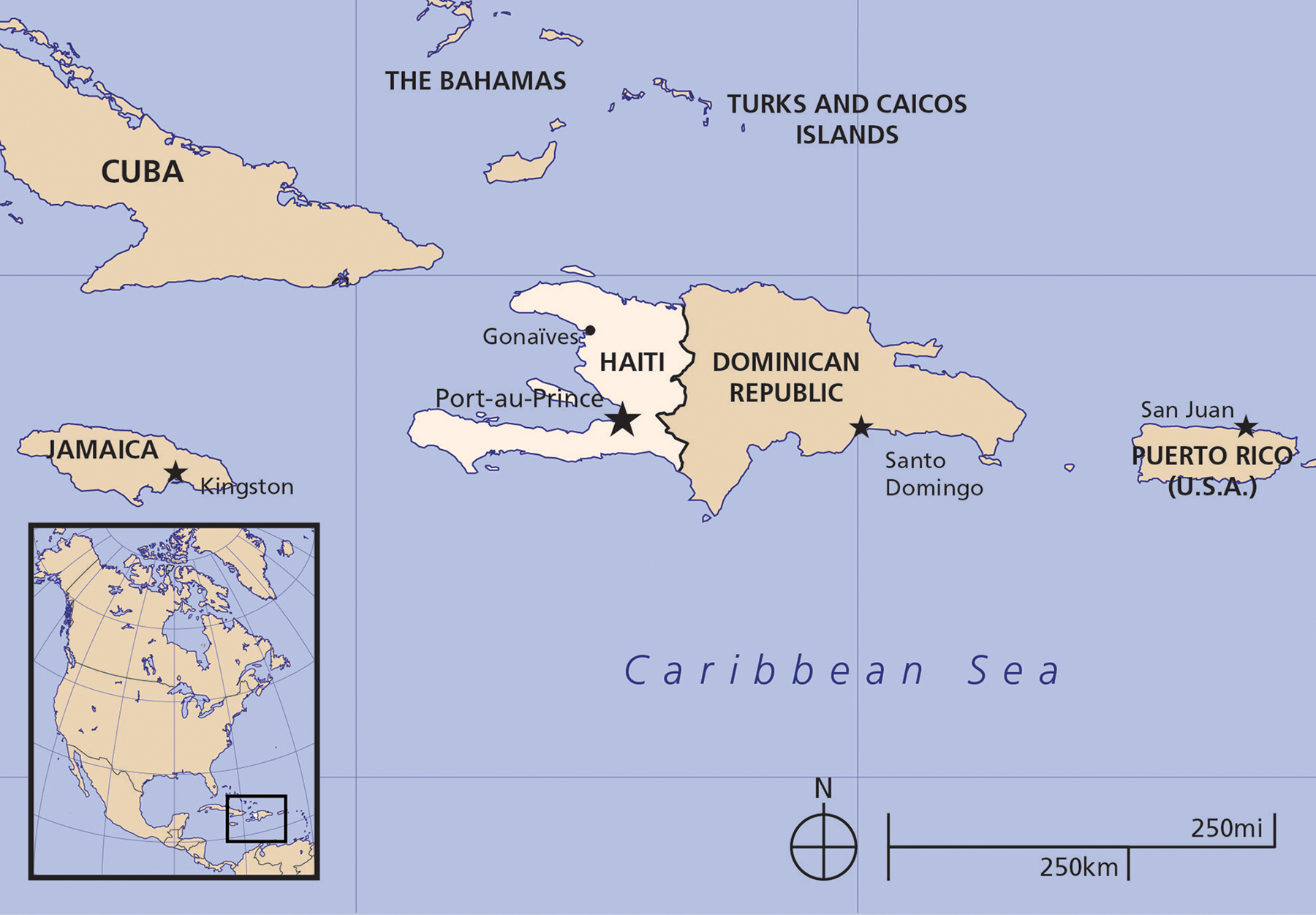

Haiti is one of two separate countries that occupy the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea. Haiti was a French sugar plantation colony populated largely by enslaved people that won its independence from France in 1804. The second country, the Dominican Republic, was a Spanish colony for three hundred years and became independent from Spain in 1820. Although these countries share the same island and have populations of around eleven million people each, there are major differences between the two.

One of the most important differences is that Haiti is a much poorer country than the Dominican Republic. Nearly 60 percent of Haiti’s population lives on less than $2.41 a day—which is a far higher percentage of people than in the Dominican Republic. A number of factors led to these differences in levels of poverty. International powers, such as Spain, France, and the United States have interfered in both countries’ affairs over time and in different ways.

For example, following the Haitian Revolution, France refused to recognize Haiti’s independence until 1825. In return for official recognition, France’s leader, King Charles X, forced Haiti to agree to pay for the damages caused to French interests during the Haitian Revolution—an amount equaling roughly twenty-two billion U.S. dollars today. The “damages” were meant to cover French plantation owners’ loss of property—including enslaved people.

Haiti’s debt to France strangled the Haitian economy. By 1913, more than 80 percent of Haiti’s annual national income was used to pay for its debt. In 1915, the United States invaded Haiti and set up an American military occupation of the island that would last until 1934—all to force Haiti to pay back debts to U.S. and French banks. Haiti’s leaders eventually succeeded in paying off the full debt and all its interest in 1947.

Some scholars suggest that race and racism has also led international powers to discriminate against Haitians. (Haiti is about 95 percent Black.) These factors and many others set the stage for economic inequality between the two countries.

Comparing Haiti and the Dominican Republic helps show how poverty increases vulnerability to the effects of climate change. In addition, the case of Haiti illustrates how poverty can limit the capacity to adapt to climate change.

| Haiti | Dominican Republic | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | 11.3 million | 10.6 million |

| GDP per Capita | US $1,801 | US $19,182 |

| Life Expectancy | 64 years | 78 years |

| CO2 Emissions per Capita | 0.3 metric tons | 2.1 metric tons |

Sharp differences in the effects of extreme weather on Haiti and the Dominican Republic show how poverty can contribute to vulnerability of the population. The location of the island of Hispaniola in the Caribbean Sea places it in the path of hurricanes and tropical storms. Climate change contributes to more intense storms that come with strong winds and high levels of rainfall. When a powerful hurricane named Jeanne tore over the island in 2004, it killed more than three thousand people in Haiti but fewer than twenty-five people in the Dominican Republic. Flooding caused many of the deaths in Haiti. During the storm, torrential rains and walls of mud poured down Haiti’s steep hillsides and collected in rivers that gushed into the city of Gonaïves, where many of the deaths occurred. The storms destroyed crops, contaminated water supplies, and left more than 250,000 people in Haiti homeless.

It was raining when we went to sleep. We were woken up by water in our beds, and in no time it was like an ocean invading us…. I heard my father calling for help. He couldn’t move because he was handicapped. When I managed to get to his room, he was already taken by the water.”

Nostra Gosette, a sixteen-year-old survivor of Hurricane Jeanne reflecting in 2005 on her experience

There is a direct link between poverty and the amount of damage that occurred in Haiti because of Hurricane Jeanne. It is because of this link that people in Haiti were more vulnerable than those in the Dominican Republic. Haiti’s steep and hilly terrain was once covered with trees and rainforests that absorbed the rain and reduced the threat of mudslides caused by tropical downpours. Today, parts of Haiti are largely deforested because trees are used as the leading source of energy. Deforestation has put hillsides at a greater risk of soil erosion and the kinds of flash flooding that led to the deaths of so many people during Hurricane Jeanne. In contrast, because of the availability of electricity and other fuel sources in the Dominican Republic, the people there do not rely on harvesting trees for energy and do not face problems of such severity from deforestation.

The crucial thing, because we’re a country facing both an energy security crisis and a food security crisis, is how can we reconcile energy security and food security?”

Gael Pressoir, Haitian nonprofit founder and business owner, November 2009

Constant erosion of fertile soil in Haiti makes planting trees to reforest the land more difficult. In addition, the fact that most farmers do not own the land they farm means that they often have little incentive to build embankments or to plant and protect trees to limit erosion and flooding. Farmers face more challenges as erosion worsens, because the best soil has been washed away.

Farmers will also have to contend with other effects of climate change. Rising sea levels will lead to increased storm surges of saltwater in low-lying agricultural areas. Saltwater can contaminate fresh water sources and damage soil, making growing crops more difficult. Furthermore, higher temperatures and greater variation in rainfall patterns in Haiti have already led to more droughts during the dry season and more intense rain during the rainy season. These changes present challenges to farmers who lack access to information about new rainfall patterns and struggle to find the means necessary to adapt to changing growing seasons.

Looking to the future, reduced agricultural production due to climate change is one of the most serious issues facing Haiti. The country’s economy depends on farming, and about 40 percent of Haitians work in agriculture. Damage to Haiti’s farms and crops results in food scarcity and increases in the cost of basic goods for Haitians.

Haiti has developed a NAPA (National Adaptation Programme of Action) to address its vulnerability to climate change. As the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, it needs outside funding to implement the program.

The NAPA prioritizes strengthening the Haitian government’s ability to anticipate and respond to the effects of climate change. For example, improving disaster preparedness is crucial, as is providing access to clean water sources and electricity. Other goals include reducing vulnerability to flooding through forest restoration, educating farmers about climate change and improving agricultural practices, and increasing living standards in rural areas. Ultimately, the most ambitious goal is to relieve poverty in order to reduce vulnerability to climate change.

While this process of planning is important, actually implementing a NAPA is particularly challenging in Haiti. Haiti’s government struggles to provide even the most basic services to its citizens and depends on the UN, other countries, and many international NGOs for help with climate change adaptation. This creates confusion, as different organizations sometimes fail to coordinate their activities or prefer to fund their own adaptation projects rather than those proposed by the Haitian government. NGOs sometimes lack knowledge about local communities, who in turn mistrust the NGOs. Uncertain political conditions in Haiti have at times made international donors reluctant to contribute funds. Other issues also complicate the response. For example, many Haitian farmers, facing more immediate problems like daily hunger, do not prioritize learning about and adapting to climate change.

Poverty both makes Haiti more vulnerable to climate change and makes responding more challenging. This creates a cycle that is difficult to break.

Nigeria is a multiethnic, multireligious country in West Africa. It is situated directly south of the Sahel (the transition area between the Sahara Desert and sub-Saharan Africa), and its southern border is located on the coast of the Gulf of Guinea.

Nigeria is one of the top oil producing countries in the world, processing more than two million barrels of oil per day. Competition over profits from oil has caused a great deal of political and social conflict in Nigeria. The practices of oil companies like Shell and Chevron in the region have received criticism from local communities. Nigerian women have played an important role in protesting oil companies in the Niger Delta in some cases. In addition to shedding light on the tensions between powerful industries and their role in causing climate change, looking closely at Nigeria can help us understand the relationship between gender and responses to climate change.

| Nigeria | |

|---|---|

| Population | 201 million |

| GDP per Capita | US $5,348 |

| Life Expectancy | 54 years |

| CO2 Emissions per Capita | 0.65 metric tons |

The geographic variation in Nigeria means that it is vulnerable to a wide range of effects of climate change. The North already experiences severe heat and water scarcity. Increasing temperatures will lead to extreme drought and heat-related illness, driving the people of this region into a state of desperation. In the South, high concentrations of people living along the coast are vulnerable to flooding as sea levels rise. Slums and other inadequate forms of housing are scattered along the most hazardous parts of coastal areas and wetlands. Here, poor people live in constant danger of flooding, particularly as their homes cannot withstand extreme weather. Poor people in Nigeria face some of the greatest vulnerability to climate change.

Around the world, poor women face this vulnerability to the extreme. In certain parts of Nigeria, this is also true. Many women in poor communities play a major role in the agriculture industry, farming in order to feed their families or to make a profit. These roles often expose women to greater impacts from climate change. For example, it is typical in rural areas for women to have the responsibility of collecting water for the household. As temperatures increase and water sources become more scarce, women will have to walk greater distances (often in extreme heat) to access water. Women face these and other risks to a greater degree than men in poor communities throughout the world.

The Nigerian government has some climate change-related policies. Local populations and nongovernmental organizations also play a vital role in responding to the threat of climate change. In the North, for instance, local communities are sharing insights on new agricultural practices as well as resources, such as seeds for growing crops, to help each other adapt to changes in climate. In the Niger River Delta, activists and local communities have also contributed greatly. Reflecting the relationship between gender and climate vulnerability, some of these groups have been influenced in important ways by women.

In the 1990s, communities in the Niger Delta (an area rich in oil reserves) began to express discontent with the practices of large oil companies and the Nigerian government. Local people disapproved of the way that oil profits were distributed. To further complicate the matter, oil corporations were also degrading the environment in the Delta. Most notably, they were illegally burning flares of natural gas during oil drilling. In Europe and North America, the natural gas that is released during oil extraction is collected and used in multiple ways, such as for generating electricity or making chemicals. In Nigeria, however, oil companies burned the gas because this was cheaper. The flares also released toxic gases that threatened public health in the surrounding villages.

Tensions rose to new levels in 1995, when a group of activists from the Niger Delta were hanged by the military dictatorship after being charged with crimes that most people believed were fraudulent.

Shell’s day will surely come for there is no doubt in my mind that the ecological war that the Company has waged in the Delta will be called to question and the crimes of that war be duly punished.”Ken Saro-Wiwa, Nigerian writer and environmental activist, on being sentenced to death by hanging, 1995

Later, during a nonviolent protest in 1999, police and government soldiers brutally attacked protesters and targeted the women who were involved. In general, women in the region also faced sexual violence at the hands of members of the Nigerian military. In response to the situation in the region, women’s organizations banded together to fight the oil companies that were funding the government and its use of violence. During a ten month occupation of Shell’s facilities, they demanded that flaring in Nigeria be completely phased out by 2007.

Throughout the early 2000s, groups in the Niger Delta—including some women’s groups—and their international partners continued to demand changes in the practices of oil companies operating in the Delta. These women’s groups were eventually able to persuade the Nigerian courts in 2006 to demand Shell end all flaring in the western part of the Niger Delta. In spite of this, the practice of gas flaring continues in Nigeria.

Nigerian protests against oil companies like Shell show that while in many cases women are particularly affected by climate change, they also have played an important role in resisting climate change and working for improvements. To this day, women activists work to demand climate justice in Nigeria.

The 2018 IPCC report warning that we only have 12 years to act inspired me to join the Fridays for Future [youth protest] movement. The African continent is the most vulnerable to the climate crisis, and we can’t go on seeing our future being jeopardized. I visit communities, schools, religious places and public places to speak to people about the climate crisis and how important environmental justice can be for their communities. It does not matter what race, sex, tribe, country or age anyone is. Everyone can get involved in the fight for climate justice. What matters most is where we are going and what we want to achieve.”

Oladosu Adenike, a Nigerian climate activist, October 28, 2019

Bangladesh is among the most densely populated countries in the world. One of the most prominent geographic characteristics of Bangladesh is the Ganges Delta, where the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna Rivers come together. This merging of the three rivers means that the area has richly fertile soil and expansive wetlands (areas of swamps and marshes).

The combination of this distinctive geography and the large Bangladeshi population has resulted in people living on chars, which are small river islands. While the economy of the country is based largely on manufacturing—with clothing and textiles as key exports—small-scale agriculture is the typical way of life on the chars. Char residents (as well as other rural Bangladeshi populations) live very interdependent and communal lives, often sharing resources and working together in the face of challenges. Because of this, Bangladesh provides many examples of locally initiated responses to climate change.

| Bangladesh | |

|---|---|

| Population | 163 million |

| GDP per Capita | US $4,951 |

| Life Expectancy | 72 years |

| CO2 Emissions per Capita | 0.53 metric tons |

Because it is dominated by rivers and coastlines, Bangladesh is one of the world’s most vulnerable countries to flooding. It is frequently hit by severe storms, and rises in sea level quickly envelop the already scarce and overpopulated land. Saltwater has already begun to seep into sources of drinking water and into farmers’ soil, making growing certain crops, such as rice, much more challenging. As climate change causes rising sea levels and intensifying storms, Bangladesh will face more weather-related deaths, declines in public health, and too little land for a growing population.

Inhabitants of chars and wetlands are particularly vulnerable, and some of the islands are fully submerged for large parts of the year. This means that char residents have to migrate to other islands or the river shores until they can return to their homes. Their only other option is to move to cities, where urban slums are rapidly growing. Both in these quickly built slums and on the chars, there is no infrastructure for sanitation or clean drinking water. Waterborne diseases like cholera are common and spread quickly. Because the poorest people live in the most vulnerable areas, the effects of climate change hit them especially hard. These people are unlikely to be able to afford health care or to replace possessions lost in extreme weather.

In Bangladesh, as in many countries in the global South, responses to climate change tend to rely on reducing poverty in order to decrease vulnerability. To do this, Bangladesh has focused primarily on education. Improving education helps increase Bangladesh’s resilience to the effects of climate change in various ways. Better education allows for more career opportunities. This means that educated young people can pursue careers in sectors like manufacturing, which are less sensitive to a changing climate than sectors like agriculture. Bangladesh has also promoted a link between education and migration. In attempts to reduce the pressure of a large population living on increasingly scarce land, Bangladesh has pursued what some call an “intentional brain drain.” The goal is to educate Bangladeshi youth so that they can easily emigrate to other countries that need people with their qualifications.

In addition, the Bangladeshi government was one of the first to create a National Adaptation Programme of Action (NAPA) in 2005. Yet the country’s national government quickly realized that the NAPA would not be adequate in addressing the threat posed by climate change. As a result, Bangladesh created a more comprehensive national strategy and action plan for dealing with climate change. This plan included setting up two funding systems—one for wealthier countries to help fund climate change mitigation and adaptation efforts in Bangladesh and another for the Bangladeshi government to fund its own projects to counter climate change.

My request to world leaders is that our environment remain in good shape. My call to the developed world is that they should take care when it comes to us. We want a future where we can live peacefully with our children. [World leaders] should think about us. They should limit their activities that cause climate change. They should be reducing these activities, and think about our benefits so we would be able to lead a good life in this world.”

Helena Bilkish, a Bangladeshi woman speaking about the effects of climate change on people living in Bangladesh, March 8, 2019

Many of the most effective adaptation efforts in Bangladesh have originated within poor communities. The dedication and knowledge of these communities have resulted in small scale adaptation efforts that have made Bangladesh a leader in the field. Ranging from floating farms that defy the restrictions of limited land to innovations in how homes are built to resist flooding, adaptation in Bangladesh has been an astounding example of community-led development.

In Kundetar Village, for example, a committee of local women has partnered with Gana Unnayan Kendra (a local NGO) and Oxfam to establish more effective disaster preparedness. These women have created a local network within their community for anticipating extreme weather events. They constantly listen to both Bangladeshi and foreign radio stations for any indication that bad weather could be approaching. If they do expect extreme weather, the women place important tools and resources in high places so they are accessible if flooding occurs.

An important benefit of locally-led adaptation is that it is defined by the very people who are experiencing the problems. This has not necessarily been the case with the national climate change response in Bangladesh. When creating its NAPA, the Bangladeshi government failed to adequately involve local populations in its deliberations. As a result, the priorities of the NAPA did not directly match the priorities of the Bangladeshi people, particularly the poor. Local efforts allow people to engage in adaptation in a way that aligns with their needs and interests. Local adaptation strategies also tend to be more easily shared because they are communal in nature and require the participation of all local inhabitants.

It’s difficult for the people of many countries like Bangladesh to face the double burden of poverty and impacts of climate change.... For the sake of sustainability of environment and development, we need to act now without delay, individually, locally, nationally, regionally, and globally.”

Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina of Bangladesh, 2013

Local adaptation efforts are not sufficient in the fight against global climate change. There are often funding shortages for the widespread use of adaptation techniques, and poor, local communities often lack the political power to demand climate change policy from the national government or international community. Furthermore, these populations often cannot implement many climate change mitigation strategies because they are responsible for so little of the world’s greenhouse gas emissions.